7 Acute Limb Ischemia (ALI)

The pre/post questions are listed below. They are all multiple choice questions with a single right answer. To best guide your learning, we have hidden the answers in a collapsible menu. Before reading the chapter, we suggest giving the questions a try, noting your answers on a notepad. After reading the chapter, return to the questions, re-evaluate your answers, and then open the collapsible menu to read the correct answer and discussion. Do not fret if you have difficulty answering the questions before reading the chapter! By the end of the chapter, we are certain you will have covered the knowledge necessary to answer the questions. There will be a teaching case at the end of the chapter. This is another opportunity to exercise your new knowledge!

Pre/Post Questions

Case Based Questions

- A 61-year-old man with a history of heavy smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and peripheral arterial disease with intermittent claudication presents to the ED with 3 hours of severe, acute-onset pain in his right foot. He takes aspirin daily, a beta-blocker for his hypertension, and metformin for his diabetes. His right foot is cool compared to his left foot. A thorough physical exam reveals no palpable pulses or audible doppler signals in his dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial arteries in the right foot. In addition, he has loss of fine touch, and proprioception to the ankle. He also has weakness with plantar/dorsiflexion of the toes in the right foot. Based on Rutherford’s classification of acute limb ischemia, what category of acute limb ischemia does this patient have?

I

IIa

IIb

III

- A 62-year-old man with diabetes, hypertension, congestive heart failure, and peripheral arterial disease presents to the ED with rest pain,decreased sensation up to his calf, and difficulty with movement of his toes in his left leg. He has been told he has acute limb ischemia and requires intervention. While you are obtaining consent for surgery, the patient asks about his chances of survival without intervention. Which of the following statements applies to his situation?

The 5-year mortality rate is high secondary to his comorbidities, regardless of his acute limb ischemia.

The 30-day mortality rate is increased (approximately 60%) if no revascularization is performed.

The mortality rate of acute limb ischemia approaches 20% overall.

The mortality rate is not affected by his treatment of his ischemic limb.

- A 56-year-old man with chronic rate-controlled atrial fibrillation stopped coumadin prior to a colonoscopy 1 week ago. He is otherwise healthy and takes no other medications. He presents with pain in his left calf after walking two miles in 90 degree temperatures. He is found to have both absent pulses and doppler signals in both his dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries in that leg. This is accompanied by pallor and pain. What is the most likely etiology?

Embolus as a result of his atrial fibrillation.

Embolus that originated from an aortic plaque.

Paradoxical embolus.

Thrombosis from hypotension.

Thrombosis from hypercoagulability

- A 68-year-old man with a history of uncontrolled diabetes, atrial fibrillation, and hypertension presents to the emergency department for pain in his left leg. A computed tomography angiogram shows a cutoff sign at the left femoral at the bifurcation of the superficial femoral artery and the profunda femoris artery. Which of the following physical examination findings would be seen in this man if your suspected etiology is an acute arterial embolism?

Reproducible buttock pain after ambulation, atrophy of calf muscles, erectile dysfunction, and absent femoral pulses.

Bilateral decreased foot sensation, bilateral lower leg pain that is relieved with elevation, and palpable pedal and femoral pulses.

Calf pain that is reproducible after ambulating 50 feet, which resolves with rest, monophasic pedal signals, and palpable femoral pulses.

Decreased foot and lower leg sensation, lower leg pain, leg pallor, decreased temperature compared to contralateral leg, and absent pedal and femoral pulses.

Loss of sensation over the foot, complete loss of motor function at the ankle joint, and mottling of the skin on the foot, absent pedal pulses, and palpable popliteal and femoral pulses.

- A 74 year old male with a history of metastatic pancreatic cancer, hypertension, prior HTN, hyperlipidemia presents to the ED with acute onset pain in his right leg. CT scan shows cutoff sign at the P3 segment just proximal to the right tibial trifurcation. In addition to pain, the patient endorses decreased sensation of his right lower leg. On exam his right leg is cool to touch and has absent pedal and popliteal doppler signals. What is the first step in management of this patient?

Emergent open surgical embolectomy with bypass

Catheter based thrombolysis

Percutaneous fogarty thrombectomy

Start a therapeutic heparin drip

Introduction

Acute Limb Ischemia (ALI) is a vascular emergency characterized by a sudden decrease in limb arterial perfusion. (Creager, Kaufman, and Conte 2012) Without timely operative revascularization, it can lead to limb loss and death.

Recent data indicates an incidence of approximately 1.5 cases per 10,000 people annually, with a 9% 30-day mortality rate and a 12.7% 30-day amputation rate despite early revascularization. (Olinic et al. 2019)

ALI is commonly caused by arterial embolism or thrombosis, with risk factors including smoking, diabetes, age, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, family history of vascular disease, and obesity. (Sidawy and Perler 2023a) (Smith and Lilie 2024a)

Clinical manifestations vary based on the affected artery and collateral blood vessels, with the 6 P’s (pain, pulselessness, pallor, poikilothermia, paresthesias, and paralysis) serving as diagnostic indicators. These symptoms make sense. If you have no flow, there will be no pulse. With no pulse, there will be no red blood (pallor) or warm blood (poikliothermia) in the affected limb. Lack of blood flow causes ischemia leading to pain, nerve ischemia/death (paraesthesia), and eventual paralysis. Review a pictogram of the 6 P’s here.

CT angiography is the preferred imaging modality, aiding in both diagnosis and intraoperative strategy. Treatment options range from anticoagulation alone to open or endovascular surgery, depending on the severity of ALI. (Sidawy and Perler 2023b)

The 6 P’s are highly testable and extremely important to recognize. Again, they are:

Pain (sometimes lessenes when limb is in a dependent position, i.e. gravity help blood flow)

Pulselessness

Palllor

Poikliothermia (i.e. cold to touch)

Paresthesia (replaces pain in later stages)

Paralysis (final stage)

Most patients initially present with pain, pallor, pulselessness, and poikliothermia.(Smith and Lilie 2024b)

Etiology

As briefly mentioned in the introduction, ALI is caused by a sudden reduction in blood supply to the affected limb. The two major causes of ALI are embolism and thrombosis.

Embolism

Embolic events occur when material, typically clot, dislodges from a source and travels in the arterial system until it deposits in a vessel causing an obstruction. Emboli typically get lodged at arterial bifurcation sites or in atherosclerotic vessels. For example in the lower extremity, clot commonly lodges at the bifurcation where the common femoral artery divides into the superficial femoral artery and profunda. Patients who have acute limb ischemia due to embolic sources typically have severe symptoms due to lack of collateral development (N.B. collateralization is a common finding in patients with chronic limb ischemia).

Embolic events can typically be categorized into those that come from cardiac and those that come from noncardiac sources.

The most common etiology of cardiac emboli is atrial fibrillation, a condition that causes uncoordinated contractions of the atrium leading to stasis of blood and clot formation (typically in the left atrial appendage) which can then embolize. Other common cardiac sources include, but are not limited to, left ventricular aneurysms, mural thrombi in the ventricles, endocarditis, and valvular disease.

Non-cardiac embolism can be caused by atheroembolism, which typically occurs in patients with a history of atherosclerotic disease in arteries such as the aortic arch or descending thoracic artery. This occurs when fragments of plaque or thrombus detach from the walls of the affected arteries and travel through the arterial system similar to a cardiac emboli. These cases may be spontaneous or secondary to intraarterial wire or catheter manipulation. Finally, patients with hypercoagulable conditions may develop an aortic mural thrombus that can embolize to a limb.

Thrombosis

Thrombosis, the formation of a blood clot within an artery, can be due to various causes with rupture of a plaque being the most common. In the case of atherosclerosis, an acute arterial occlusion develops on a severe stenotic lesion. Symptoms of ALI in this case are less severe and more progressive in nature than symptoms caused by emboli as the body has had ample time to develop a robust collateral circulation. Vasospasm due to secondary Raynaud’s disease can result in digital ischemia and requires timely diagnosis and treatment with anticoagulation, thrombolytics, vasodilators, or prostanoids. Thrombosis within a vessel can also be due to a hypercoagulable state. This is usually in the case of malignant disease which leads to venous thrombosis but can also be due to heparin induced thrombocytopenia. Finally, vascular patients in particular may develop thrombosis from an aortic dissection or bypass graft occlusion.

Diagnostics and Imaging

Clinical Diagnosis

The first step in the diagnosis of ALI is a thorough history and physical exam of the patient. While taking a history, it is important to elucidate the duration and extent of symptoms, cardiovascular risk factors, and past medical history from the patient. Furthermore, it is crucial to establish whether the patient is taking any anticoagulant medications, and if they are, ascertain the timing of their most recent dose.

As mentioned above in the introduction, the 6 P’s (pain, pulselessness, pallor, poikilothermia, paresthesias, and paralysis) can be used as a guide in the diagnosis of ALI. However, symptoms can range depending on the severity of ischemia and pre-existence of collaterals. It is important to note that ALI presenting with less severe symptoms may be misdiagnosed as musculoskeletal disease, sciatica, or other generalized causes of limb pain.

Physical exam findings of the affected limb are essential for diagnosis and classification with regards to severity and need for a revascularization procedure. Extremely pale skin color in the affected limb is a sign of total ischemia; this finding may be more difficult to elicit based on the patient’s baseline skin color. Loss of sensation and more specifically loss of fine touch and proprioception should be evaluated. Muscle tenderness, particularly in the calf when a lower extremity is involved indicates advanced ischemia. Finally, a vascular exam with a doppler should be performed and can be both diagnostic and reveal the level of occlusion.

The gold standard of classifying ALI of the lower extremity and determining need for intervention is based on this combination of sensory/motor clinical findings and a vascular exam with doppler findings.

As indicated in table 1 below, patients who are classified as Class 2 or above will require surgical intervention.

Timing of treatment is an important consideration; patients who fall under class 2a are marginally threatened and do not require immediate intervention versus those who fall under class 2b and 3.

| Rutherford Class | Sensory Impairment | Motor Impairment | Doppler Signals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class I (No immediate threat) | None | None | Arterial: audible Venous: audible |

| Class IIa (Marginally Threatened) | Minimal | None | Arterial: audible Venous: audible |

| Class IIb (Immediately Threatened) | Involves forefoot with possible rest pain | Mild to moderate | Arterial: absent Venous: present |

| Class III (Irreversible ischemia) | Insensate | Severe, rigorous | Arterial: absent Venous: absent |

Imaging

Imaging may be utilized in the diagnosis of ALI cases that do not require immediate intervention and transport to the operating room.

CT angiography is the imaging modality of choice as it is easily and quickly accessible in most emergency departments; CTA reads can aid in both diagnosis and preoperative planning.

Ultrasound may also be useful in certain instances such as rapid, bedside imaging.

Transfemoral angiography or angiography through an alternative access vessel site is typically utilized at the beginning of an endovascular procedure for intraoperative planning once a diagnosis of ALI has been established.

Treatment

Initial management

AAs mentioned in the previous section, treatment and timing of treatment for ALI depends on the Rutherford class. However, there is a universal set of things that should be done for any patient regardless of their class. Initiation of systemic anticoagulation with heparin or a direct thrombin inhibitor in the case of a heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is always the first step in management. Heparin may even be started during the diagnostic work-up if there is a high clinical suspicion of ALI. Initial labs that should be ordered include a CBC, CMP, baseline fibrinogen, and a type and screen.

Operative management

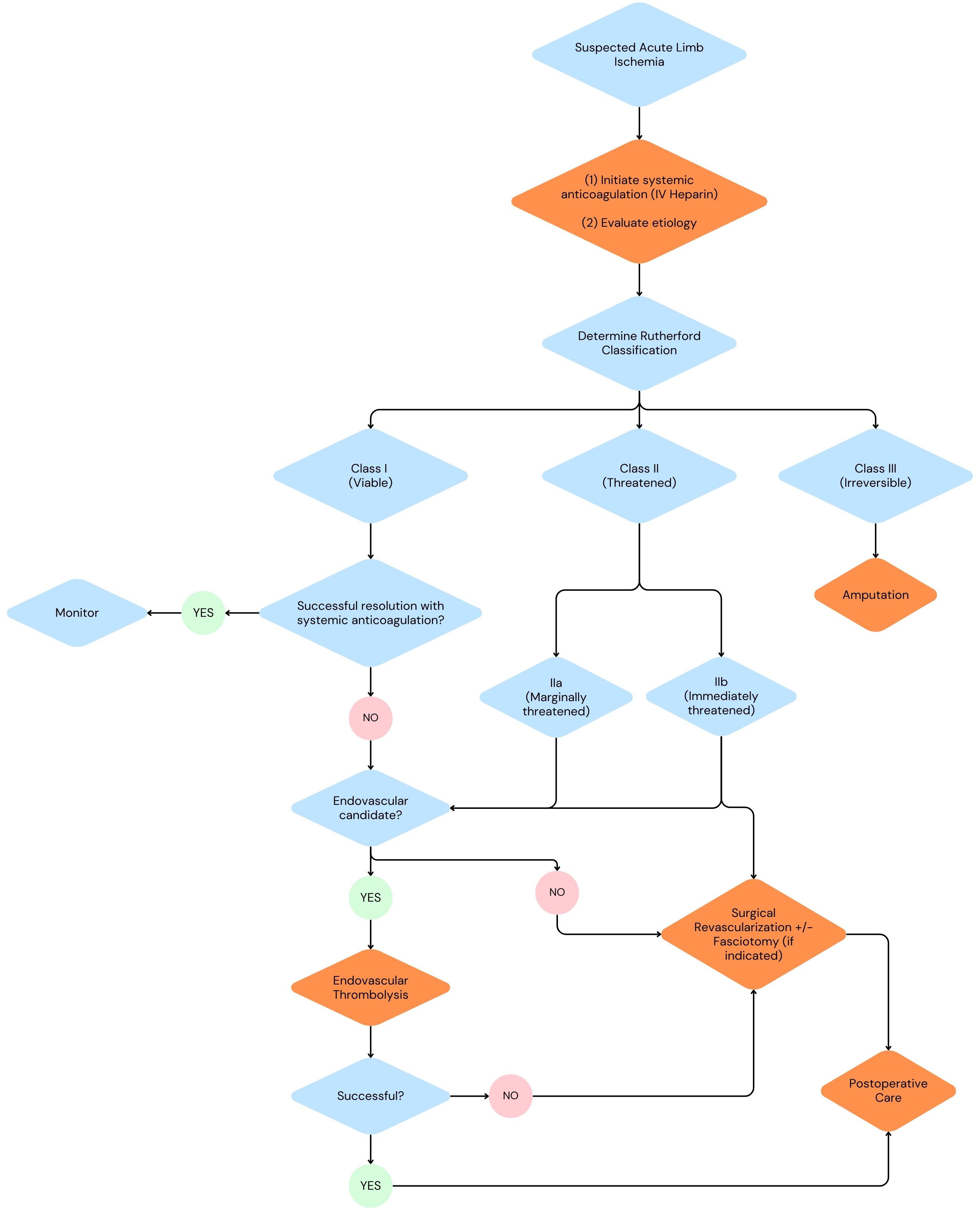

As far as surgical options go, ALI can be managed with endovascular surgery, open surgery, or through a hybrid approach. The algorithm above shows considerations for when to pursue an endovascular vs. open approach.

Surgical Revascularization

Surgical revascularization options include catheter embolectomy/thrombectomy, surgical bypass, endarterectomy, and hybrid procedures if indicated.

Embolectomy/thrombectomy with a Fogarty embolectomy catheter has remained the gold standard for treatment of both acute and chronic thromboembolic disease. The use of a Fogarty embolectomy catheter requires a surgical cutdown depending on the location of obstruction, control of inflow and outflow branches, therapeutic anticoagulation, and an arteriotomy. After the arteriotomy is made, the catheter is passed both proximally and distally until all of the thrombus is removed and there is confirmation of pulsatile inflow and distal back-bleeding. The last step is an on-table angiogram to confirm the patency of the treated vessels.

Arterial bypass is an option in cases where catheter thrombectomy/endovascular intervention fails or when a patient has known PAD and is presenting with an acute-on chronic picture as it may provide a more long-term solution.

Thromboendarterectomy is typically performed as part of a hybrid procedure in cases of ALI. It is often utilized to improve flow in cases of common femoral artery acute in situ thrombosis in chronic atherosclerotic disease, to collaterals, and to inflow and outflow of bypass graft anastomoses, An example of a case utilizing a hybrid approach would be if a patient presented with ALI and was found to have a bypass graft occlusion. The occlusion is treated with a traditional embolectomy using a Fogarty balloon and a common femoral endarterectomy is additionally performed to improve graft inflow.

Endovascular Management

Endovascular surgery for the management of ALI provides minimally invasive options for patients who are not good candidates for open revascularization. Endovascular surgical options include catheter directed thrombolysis, mechanical thrombectomy, or pharmacomechanical thrombectomy and there are numerous devices on the market for the application of these therapies.

In catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT), utilized in viable (class I) and marginally threatened (class IIa) cases of ALI, a tPA infusion catheter is inserted into a selected artery percutaneously and provides targeted anticoagulation to the affected lesion reducing systemic effects. The lytic catheter is positioned just distal to the end of the thrombus and proximal to the origin of the thrombus. The lytic agent is initiated at placement and continues over a 10-12 hour period with fibrinogen level monitoring every 4 hours; therapy should be discontinued if fibrinogen levels drop <100. Major contraindications for this procedure include a head injury, intracranial surgery, spine surgery, or stroke within the last 3 months, an active bleeding disorder, a GI bleeding disorder within 10 days, a cerebrovascular accident within 6 months, known intracranial aneurysm, tumor, or vascular malformation.

*Mechanical thrombectomy uses aspiration, hydrodynamic forces, or mechanical/rotational forces to clear a thrombus. The procedural steps are similar to catheter-directed thrombolysis in terms of percutaneous access and cannulation of the target vessel. This procedure utilizes an aspiration mechanical thrombectomy catheter to simultaneously provide fragmentation and aspiration to restore arterial flow.

Pharmacomechanical thrombectomy is a very similar concept as mechanical thrombectomy. In addition to mechanical clot extraction, it applies thrombolytic therapy with a lytic agent . The advantage of this therapy in comparison to catheter directed thrombolysis is the decreased lytic dose and duration of thrombolysis required.

Other

In severe cases of ALI where irreversible tissue damage is obvious such as in patients with Rutherford III classification, primary amputation may be the most viable treatment option. With irreversible neurovascular damage and tissue necrosis, primary amputation serves to prevent further spread of tissue damage and infection.

Post-Operative Complications & Management

The major postoperative complications of ALI are systemic end organ insults from sequelae of ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury. Reperfusion resulting in rhabdomyolysis, myoglobinuria, and compartment syndrome must be monitored for. Baseline and surveillance creatine phosphokinase as well as surveillance for electrolyte abnormalities, acid base abnormalities, and urine abnormalities including hemoglobinuria, myoglobinuria, and oliguria should be performed.

Four Compartment Fasciotomy

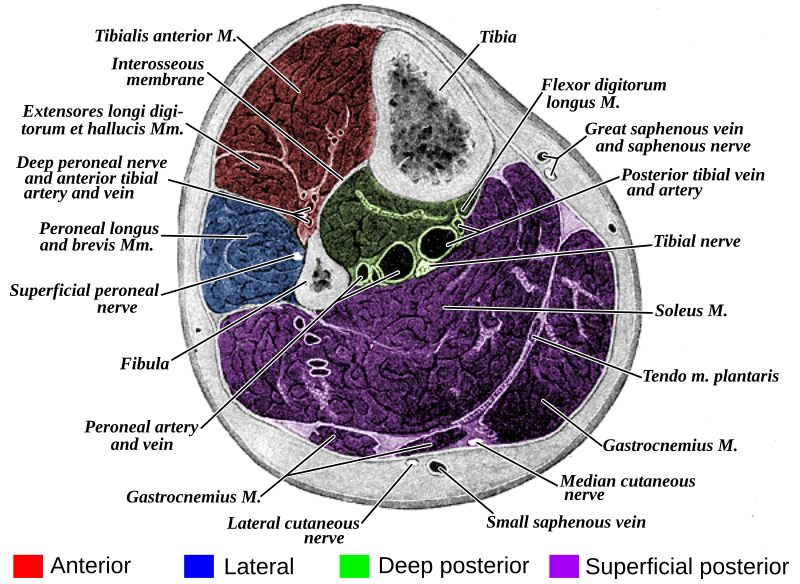

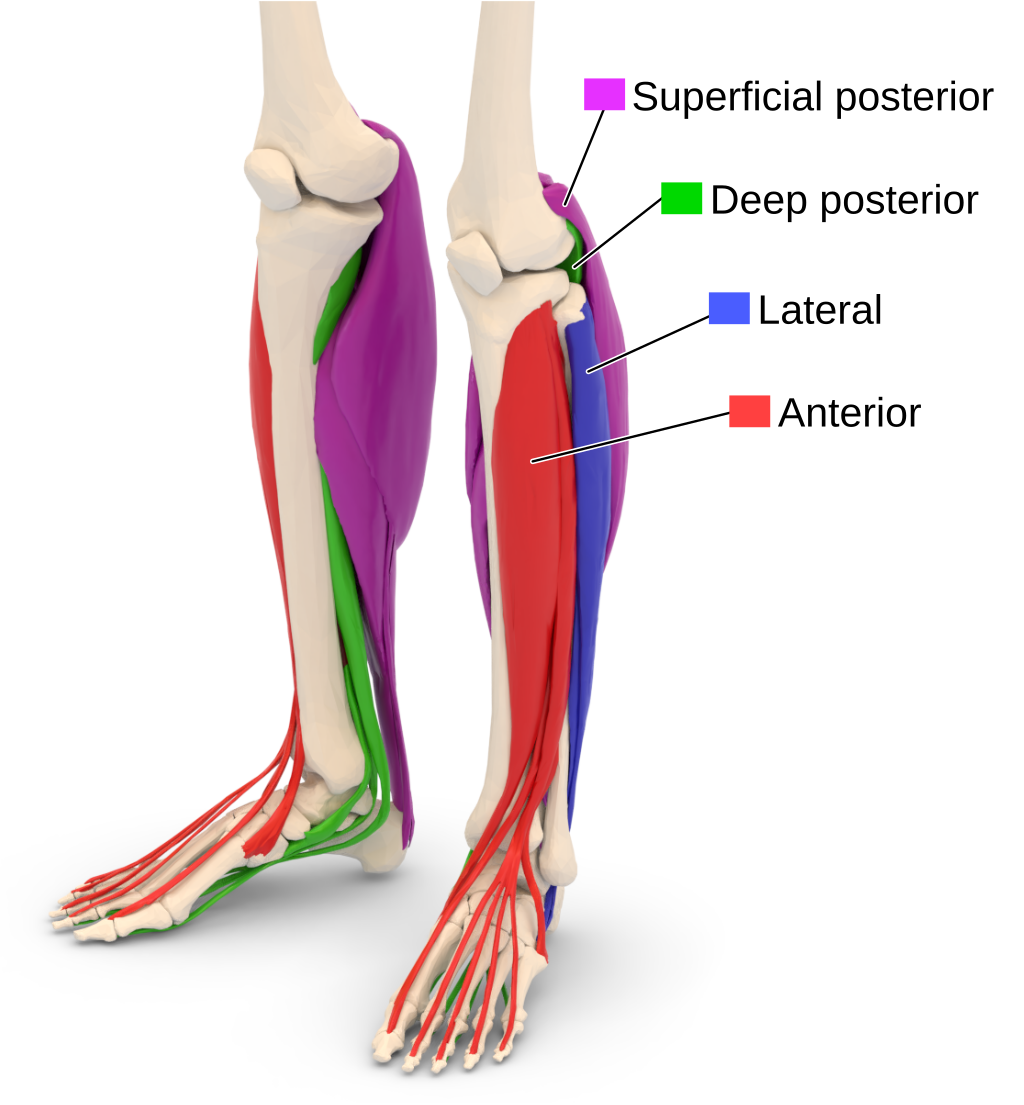

Prophylactic decompression fasciotomy is recommended in cases with greater than 6 hours of ischemia time and/or in patients with sensory and/or motor deficits. Compartment syndrome is largely a clinical diagnosis however, you can also utilize a Stryker needle as a diagnostic tool and objectively measure compartment pressures. Typically, intracompartmental pressure > 30mmHg or 30 mmHg below the patient’s diastolic blood pressure suggests a high likelihood of compartment syndrome particularly if your clinical suspicion is high. It is important to release all four lower leg compartments during fasciotomy.

There are several techniques to release the anterior and lateral compartments. The common techniques include making a 4 to 6 cm incision on the lateral aspect of the tibia between the fibula and the crest of the tibia. A plane is then developed between the skin and underlying fascia, which is then incised and released. The posterior compartment release involves making vertical incisions behind the posteromedial edge of the tibia. The great saphenous vein and the saphenous nerve are identified and protected during the posterior compartment release. A plane is again developed between the skin and fascia and the fascia is incised to release the compartment. The tibial attachments of the soleus are taken down in order to expose the deep posterior compartment, after which the fascia overlying the flexor digitorum logus is incised to release the deep posterior compartment.

Watch a video of a four-compartment fasciotomy here:

The contents of each compartment are often questioned and students should be familiar with the organization fo the lower limb.

| Compartment | Muscles | Neurovascular structures |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior | tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis longus, extensor digitorum longus, peroneus tertius | deep peroneal nerve, anterior tibial vessels (artery and vein) |

| Lateral | peroneus longus, peroneus brevis | superficial peroneal nerve, peroneal artery |

| Superficial Posterior | gastrocnemius, plantaris, soleus | sural nerve |

| Deep Posterior | tibialis posterior, flexor hallucis longus, flexor digitorum longus, popliteus | tibial nerve, posterior tibial vessels (artery and vein) |

Medical Management

Postoperative medical management will vary depending on the etiology of the acute limb ischemia incident. If the cause was determined to be embolic, long term anticoagulation with Vitamin K antagonists (VKA; e.g. warfarin a.k.a. “Coumadin”) or direct xa inhibitors (e.g. apixaban a.k.a. “Eliquis,” rivaroxaban a.k.a. “Xarelto”) should be initiated. If the patient was already on anticooagulation, the clinician should gain further insight into if and why a dose was missed and how to prevent similar events from occurring again. If the cause was thrombotic in nature, the patient should be counseled on starting best medical therapy with an aspirin and statin. In both cases, patients should have timely follow up scheduled with their vascular surgeon and primary care provider and smoking cessation should be encouraged.

Outcomes

- Patients with ALI tend to have poor long term morbidity and mortality outcomes

- Bypass for ALI is associated with increased rates of major limb loss (22.4%) and mortality (20.9%) at 1 year compared to bypass for all other reasons. (Baril et al. 2013)

- In a single institutional retrospective study, the 5-year freedom from re-intervention rate was 89.2%. The survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 87.9%, 75.2%, and 60.6%, respectively. (Eliason et al. 2003)

Surveillance

Medical surveillance following ALI discharge

After bypass or catheter based intervention, patients should resume their preoperative medications for angina, hypertension, arrhythmia, and congestive heart failure. Antiplatelet therapy is commonly utilized postoperatively and anticoagulation may be considered in addition to antiplatelet therapy based on patient specific factors such as etiology of clot, graft characteristics, and comorbidities.

Clinical and vascular laboratory surveillance following ALI discharge

Patients undergoing bypass due to ALI can follow SVS guidelines for vein grafts. (Zierler et al. 2018a)

Early postoperative baseline arterial duplex ultrasound, ABI/PVR, clinical examination with follow up at 3, 6, 12 months, and annually after.

More frequent surveillance may be considered for individuals with abnormalities on DUS

The SVS does not have standard surveillance guidelines for patients undergoing catheter based intervention for ALI.

Teaching Case

Scenario

A 73-year-old woman with a past medical history of HTN, HLD, Type 2 Diabetes, and Atrial Fibrillation (on xarelto) presents to the emergency department with severe right lower extremity pain. She states she has had this severe pain for 2 days which has progressed to the point of where it limits her mobility. She says she has tried over the counter pain medication as well as gabapentin but nothing has resolved the pain. The patient recently had a left knee replacement surgery 10 days ago. Post procedure, the patient was confused about when to resume her xarelto and as such has not been taking it.

Family Hx: Diabetes, HLD, Factor V Leiden Social Hx: Former smoker (1 pack per day for 15 years) Surgical Hx: Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, Vaginal Hysterectomy, Left Total Knee Replacement

Exam

Vitals:

Temp: Afebrile HR: 102 BP: 150/67 RR: 18 O2: 96 on room air

HEENT:

Normocephalic, atraumatic, mucous membranes moist, pupils equally round and reactive

Cardiac:

Regular rate and irregular rhythm

Pulmonary:

Abdominal:

Clear to auscultation bilaterally, no rales/rhonchi/wheezing

Vascular/Extremities:

RLE: Pale appearing foot, tender to palpation, cool to touch, delayed capillary refill Femoral: 2 + palpable Popliteal: 2+ palpable PT: non palpable, no audible doppler signals DP: nonpalpable, no audible doppler signals

LLE: Warm, well perfused, knee replacement incision site clean, dry, intact with no surrounding redness, warmth, or erythema Femoral: 2 + palpable Popliteal: 2+ palpable PT: 2 + palpable DP: 2 + palpable

Imaging

Discussion Points

However, we feel this chapter contains all the necessary information to answer the questions. If not, please let us know!

- Please explain the pathophysiology of the patient’s lower extremity pain

- Please list the patient’s risk factors for Acute Limb Ischemia

- Explain the findings on the CTA?

- What next steps should be pursued to pursue treatment for the patient?

- How timely do you need to be with regards to intervening on this patient?

- What additional imaging would help with surgical planning for the patient?

- What surgical treatment could be offered to this patient?

- What follow up labs/surveillance/counseling should be provided to this patient?

Key Articles

Creager MA, Kaufman JA, Conte MS. Clinical practice. Acute limb ischemia. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jun 7;366(23):2198-206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1006054. PMID: 22670905. (Creager, Kaufman, and Conte 2012)

Olinic DM, Stanek A, Tătaru DA, Homorodean C, Olinic M. Acute Limb Ischemia: An Update on Diagnosis and Management. J Clin Med. 2019 Aug 14;8(8):1215. doi: 10.3390/jcm8081215. PMID: 31416204; PMCID: PMC6723825. (Olinic et al. 2019)

Sidawy, A. N., Perler, B. A., & Rutherford, R. B. (2023). Rutherford’s vascular surgery and endovascular therapy. Elsevier. (Sidawy and Perler 2023c)

Smith DA, Lilie CJ. Acute Arterial Occlusion. [Updated 2023 Jan 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441851/# (Smith and Lilie 2023)

Baril DT, Patel VI, Judelson DR, Goodney PP, McPhee JT, Hevelone ND, Cronenwett JL, Schanzer A; Vascular Study Group of New England. Outcomes of lower extremity bypass performed for acute limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2013 Oct;58(4):949-56. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.04.036. Epub 2013 May 25. PMID: 23714364; PMCID: PMC3930450. (Baril et al. 2013)

Eliason JL, Wainess RM, Proctor MC, Dimick JB, Cowan JA Jr, Upchurch GR Jr, Stanley JC, Henke PK. A national and single institutional experience in the contemporary treatment of acute lower extremity ischemia. Ann Surg. 2003 Sep;238(3):382-9; discussion 389-90. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000086663.49670.d1. PMID: 14501504; PMCID: PMC1422711. (Eliason et al. 2003)

R. Eugene Zierler, William D. Jordan, Brajesh K. Lal, Firas Mussa, Steven Leers, Joseph Fulton, William Pevec, Andrew Hill, M. Hassan Murad, The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on follow-up after vascular surgery arterial procedures, Journal of Vascular Surgery, Volume 68, Issue 1, 2018, Pages 256-284, SSN 0741-5214, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2018.04.018 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0741521418308966) (Zierler et al. 2018b)

Björck, M., Earnshaw, J. J., Acosta, S., Bastos Gonçalves, F., Cochennec, F., Debus, E. S., Hinchliffe, R., Jongkind, V., Koelemay, M. J. W., Menyhei, G., Svetlikov, A. V., Tshomba, Y., Van Den Berg, J. C., Esvs Guidelines Committee, de Borst, G. J., Chakfé, N., Kakkos, S. K., Koncar, I., Lindholt, J. S., Tulamo, R., … Rai, K. (2020). Editor’s Choice - European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2020 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Acute Limb Ischaemia. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery, 59(2), 173–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2019.09.006 (Björck et al. 2020)

Additional Resources

Audible Bleeding Content

- Audible Bleeding Exam Prep: Acute Limb Ischemia Chapter

Websites

- TeachMe Surgery: Acute Limb Ischaemia

Gore Combat Manual

The Gore Medical Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Combat Manual is an informative and entertaining read intended as a vascular surgery crash course for medical students, residents, and fellows alike. Highly accessible with a thoughtfully determined level of detail, but lacking in learning activities (e.g. questions, videos, etc.), this resource is a wonderful complement to the APDVS eBook.

Please see pages 85, 98-100.

Operative Footage

Developed by the Debakey Institute for Cardiovascular Education & Training at Houston Methodist. YouTube account required as video content is age-restricted. Please create and/or log in to your YouTube account to have access to the videos.