6 Chronic Limb Threatening Ischemia (CLTI)

The pre/post questions are listed below. They are all multiple choice questions with a single right answer. To best guide your learning, we have hidden the answers in a collapsible menu. Before reading the chapter, we suggest giving the questions a try, noting your answers on a notepad. After reading the chapter, return to the questions, re-evaluate your answers, and then open the collapsible menu to read the correct answer and discussion. Do not fret if you have difficulty answering the questions before reading the chapter! By the end of the chapter, we are certain you will have covered the knowledge necessary to answer the questions. There will be a teaching case at the end of the chapter. This is another opportunity to exercise your new knowledge!

Pre/Post Questions

Case Based Questions

- A 45-year-old male with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presents to the emergency department with wet gangrene of his first, fourth, and fifth digits of his right lower extremity. He has a right dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial artery pulse. What level of amputation is appropriate in this situation?

Transmetatarsal amputation

Below-knee amputation

Through-knee amputation

Above-knee amputation

- A 72-year-old male with diabetes presents to his PCP’s office for a nonhealing ulcer to the plantar aspect of his right foot. Laboratory results and x-ray imaging are unremarkable. On examination, you note that his pulses are nonpalpable. Doppler examination reveals monophasic signals. He has necrotic, nonviable tissue to the base of the wound. There is no erythema or evidence of abscess. The patient has not been taking antibiotics. What is the most likely cause of the non-healing in this scenario?

Pressure

Infection

Inadequate wound care

Peripheral vascular (arterial) disease

- A 56-year-old male with hypertension, diabetes presents to the emergency department with redness and purulence draining from his right great toe. His heart rate is 110 beats/min, his blood pressure is 100/80 mm Hg, and his temperature is 38.5ºC. Laboratory tests show a white blood count of 14,000/µL. An x-ray of his foot is performed, which demonstrates gas in his right great toe. What is the best course of treatment?

Outpatient treatment with oral antibiotics and dressing changes.

Inpatient treatment with intravenous antibiotics alone.

Inpatient treatment with intravenous antibiotics and dressing changes.

Inpatient treatment with intravenous antibiotics and emergent surgical debridement .

- A 72-year-old female with diabetes has a chronic right heel ulcer that persists despite local wound care. A magnetic resonance imaging scan demonstrates osteomyelitis of the calcaneus, and a metal probe inserted into the ulcer can “probe to bone.” She has a palpable ipsilateral dorsalis pedis pulse. Which operation would be most appropriate?

Transmetatarsal amputation.

Below-knee amputation.

Local calcaneus excision with full-thickness skin flap.

Above-knee amputation.

- A 70-year-old male with poorly controlled diabetes and no smoking history presents to the clinic for an ischemic toe ulcer. What level of infrainguinal arterial occlusive disease is he most at risk for developing based on this history?

Superficial femoral artery disease

Deep femoral artery disease

Iliac artery disease

Aortic disease

Tibial artery disease

- A 75-year-old male with a history of migraines, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, triple coronary bypass (CABG x3), recurrent cellulitis, glaucoma and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) presents to your clinic due to pain. He has smoked approximately 2 packs per day for over 30 years. Despite smoking cessation counseling, he continues to smoke 1-2 cigarettes a day. He reports pain with walking for the past several years. After walking one city block, his calves begin to hurt. He intermittently develops toe sores and wounds that can take 1-2 months to heal. If the wound is larger, it can take 3-4 months to heal. What risk factors does this patient have that contribute to the most likely disease process?

Migraines

BPH

Glaucoma

Smoking

Cellulitis

- A 74-year-old female with a past medical history of IDDM with ESRD on dialysis, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and previous MI is referred to you for evaluation of crampy calf pain for the last 2 months with onset upon physical exertion. It has since progressed to pain at rest. You perform ABIs which reveal critical limb ischemia. Which of the following will you most likely observe when performing preoperative imaging of this patient prior to infrapopliteal bypass?

Critical occlusion of only the medial and lateral geniculate arteries.

Loss of enhancement in the region of the popliteal artery but reconstitution showing good distal vessel runoff.

Enhancement in the peroneal artery contributing to pedal circulation.

Complete lack of runoff past the region of the Hunter’s canal.

Full enhancement in the posterior tibial artery ending in the region of the medial malleolus.

Introduction

The term peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is often used interchangeably with peripheral vascular disease (PVD) when referring to arterial blockages.

Chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) is defined as the presence of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) with associated ischemic rest pain, gangrene, or lower limb non-healing ulceration for greater than 2 weeks duration

The prevalence of PAD is approximately 6% in patients aged 40 years or older in the United States. Amongst patients with PAD, 11% of patients (approximately 2 million individuals) will present with CLTI within their lifetime.(Conte et al. 2019a)

CLTI has an increased risk of amputation, cardiovascular morbidity, and mortality.

Etiology

CLTI is a severe manifestation of peripheral arterial disease (PAD), a disease caused by the build-up of atherosclerotic plaque in the arteries. The pattern of occlusive disease can be found in one or a combination of locations including the aortoiliac or infrainguinal vessels (i.e. femoral, popliteal, and tibial arteries) with varying lesion lengths. The superficial femoral artery (SFA) is the most common location where lesions occur. Amongst diabetics, it is typical to find heavier disease burdens more distally, such as the infrapopliteal, tibial vessels (i.e. the tibial trunk, anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and peroneal arteries).

Here is an image that demonstrates the various peripheral vessels that can be diseased and occluded in a patient with CLTI.

Risk factors for CLTI are the same as for PAD and include advanced age, race (with non-hispanic blacks having the highest risk), male gender, smoking, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and renal insufficiency. It is important to note that any other etiologies including venous, traumatic, embolic, or nonatherosclerotic disease processes are NOT considered a part of chronic limb-threatening ischemia.

For a more comprehensive review of lower limb arterial anatomy and PAD risk factors, please see Chapter 6.

Diagnostics and Imaging

The diagnosis of CLTI requires a prior diagnosis of PAD in association with ischemic rest pain or tissue loss. Pain should be present for more than two weeks and associated with at least one abnormal hemodynamic parameter.

A complete evaluation of patients with CLTI should include:

A good patient history

Physical examination

Noninvasive hemodynamic tests

- Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) and Pulse Volume Recording (PVR)

- Arterial Doppler Ultrasound

- Angiography

- CTA (abd + pelvis + lower extremity with triple vessel runoff)

- If necessary, invasive angiography

For a comprehensive description of the arterial patient history and physical exam, please see Chapter 3.

Patient History

- Patients may state that they have persistent pain in their legs, even at rest.

- Rest pain and nonhealing wounds are highly indicative of CLTI.

- Patients may also share experiencing rest pain in bed relieved by dangling their feet off the side of their bed. By dangling their feet over the side of the bed, gravity increases blood flow through diseased and collateral vessels thereby reducing ischemia and pain.

Physical Exam

Common physical exam findings on the lower extremities include:

Cyanosis

Cool Extremities

Hair loss

Dry skin

Muscle atrophy

Dystrophic toenails (thick toenails)

Capillary refill > 5 seconds

Non-palpable distal pulses

Non-healing wounds

Non-invasive Hemodynamic Testing

In terms of non-invasive testing, as stated above, a combination of ABI and PVR is the gold standard in establishing a diagnosis. As a review, the ABI is a non-invasive test that compares blood pressure in the ankle with blood pressure in the arm. ABIs are calculated by dividing the systolic ankle pressure by the highest systolic arm/brachial pressure (between the two arms).

An ABI value: - X > 1.2 is non-compressible, calcification of arteries

0.9 < x < 1.2 is normal

0.7 < x < 0.9 reflects a mild disease burden

0.4 < x < 0.7 reflects a moderate disease burden

x < 0.4 reflects a severe disease burden

Here is an example of ABI/PVR recordings. Patient A (left) shows a normal ABI/PVR recording, while patient B (right) shows an abnormal ABI with diminished waveforms.

Arterial Doppler ultrasound can also be utilized to evaluate blood flow and detect arterial stenosis or occlusion.

For a definitive CLTI diagnosis, pain should be present for more than two weeks and associated with at least one of the following abnormal hemodynamic parametersI:

Ankle-brachial index (ABI) < 0.5.

Absolute toe pressure (TP) < 30 mmHg.

Absolute Ankle Pressure (AP) < 50 mmHg.

Transcutaneous pressure of oxygen (TcPO2) < 30 mmHg.

Flat or minimal pulsatile volume recording (PVR) waveforms.

Angiography

CT Angiography (CTA) with tri-vessel runoff (i.e. anterior tibial, posterior tibial, peroneal arteries) of lower extremities can help identify the location(s) of disease. However, this investigation requires a contrast load and should be carefully considered for those patients with renal disease.

Lastly, diagnostic angiography is an invasive imaging technique that provides detailed information about the arterial anatomy and helps identify specific sites of blockage or stenosis. Diagnostic angiography involves the patient undergoing a femoral artery puncture to access the arterial system. Next, a series of catheters and wires are used to deliver contrast. Fluoroscopic imaging of the lower limb reveals vessel anatomy and identifies areas of stenotic disease. As arterial access is already achieved, immediate intervention may be considered including angioplasty (i.e. ballooning of stenosis) or stenting.

Classification Systems

Below, we will introduce and summarize the most common classification systems. For a high-yield summary of all classification systems, please see this paper. (Hardman et al. 2014)

The Rutherford Classification and Fontaine Grading

- The Rutherford Classification is the mainstay of diagnosing the severity of CLTI, however, Fontaine grading can also be used.

- These grading systems are based on symptom presentation. Patients with CLTI usually present with Fontaine Grade 2 or higher or Rutherford Category 3 or higher.

- Minor tissue loss is considered defined as non-healing ulcers with focal gangrene that do not exceed the foot digit.

- Major tissue loss extends beyond the transmetatarsal level with the functional foot no longer salvageable. Patients with major tissue loss most often receive amputations.

| Fontaine Grade | Rutherford Category | Clinical Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | Asymptomatic |

| 1 | Mild claudication | |

| 1 | 2 | Moderate claudication |

| 3 | Severe claudication | |

| 2 | 4 | Ischemic rest pain |

| 3 | 5 | Minor tissue loss |

| 6 | Major tissue loss |

The Wound, Ischemia, and foot Infection (WIfI) classification

- The Wound, Ischemia, and foot Infection (WIfI) classification was proposed in 2014 as an integrated lower extremity wound classification and prognositcation system. The WIfI classification was inspired by the tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system for cancer.

- Incorporating the presence and severity of lower extremity wounds, ischemia, and infection, the classification system informs providers of the risk of lower extremity amputation and potential benefit of revascularization.

- For the limb in question, a severity grade of 0 to 3 is assigned to the severity and extent of wound, ischemia and foot infection, respectively, where 0 presentes none, 1 mild, 2, moderate and 3 severe disease.

- Using the table here, the combination of these three scores assigns the limb in question to one of four threatened limb clinical stages.

- While an oversimplication, the premise of the WIfI system is that the risk of amputation increases as the disease burden of the limb in question progresses from WIfI stage 1 (very low risk) to tage 4 (high risk).

| Wound (ulcer or gangrene) | Ischemia (Toe Pressure/TcPO2 and ABI) | foot Infection |

|---|---|---|

| 0: No ulcer or no gangrene | 0: TP >= 60 mmHg, ABI >= 0.80 | 0: Not infected |

| 1: Small ulcer and no gangrene | 1: TP = 40-59 mmHg, ABI 0.60-0.79 | 1: Mild (=< 2 cm cellulitis) |

| 2: Deep ulcer or gangrene limited to toes | 2: TP 30-39 mmHg, ABI 0.40-0.59 | 2: Moderate (> 2 cm cellulitis or involving structures deeper than skin and subcutaneous tissues) |

| 3: Extensive ulcer or extensive gangrene | 3: TP < 30 mmHg, ABI =< 0.39 | 3: Severe (systemic response / SIRS) |

The SVS Guidelines Mobile App has an easy-to-use WIfI Calculator. - Apple App Store - Android Google Play

The Global Limb Anatomic Staging System (GLASS) Classification

- The Global Limb Anatomic Staging System (GLASS) is a framework to estimate the success of lower limb revascularization based on the extent and the distribution of the atherosclerotic lesion. By categorizing the patient’s lesion into one of three GLASS stages, the surgeon can predict the likelihood of immediate technical failure and one-year limb-based patency (LBP) following endovascular intervention. This information is extremely informative when planning a surgical intervention.

- To perform GLASS staging, the surgeon must obtain high quality imaging of the lower extremity to score the length and burden of disease femoropopliteal segment (FP) and infrapopliteal segment (IP).

Scoring System below (Wijnand et al. 2021)

| Femoro-Popliteal (FP) Grading | |

|---|---|

| 0 | Mild or no significant (<50%) disease |

| 1 | Total length SFA disease <1/3 (<10 cm); may include single focal CTO (<5 cm) as long as not flush occlusion; popliteal artery with mild or no significant disease |

| 2 | Total length SFA disease 1/3–2/3 (10–20 cm); may include CTO totaling <1/3 (10 cm) but not flush occlusion; focal popliteal artery stenosis <2 cm, not involving trifurcation |

| 3 | Total length SFA disease >2/3 (>20 cm) length; may include any flush occlusion <20 cm or non-flush CTO 10–20 cm long; short popliteal stenosis 2–5 cm, not involving trifurcation |

| 4 | Total length SFA occlusion >20 cm; popliteal disease >5 cm or extending into trifurcation; any popliteal CTO |

| Infra-Popliteal (IP) Grading | |

|---|---|

| 0 | Mild or no significant (<50%) disease |

| 1 | Focal stenosis <3 cm not including TP trunk |

| 2 | Total length of target artery disease <1/3 (<10 cm); single focal CTO (<3 cm not including TP trunk or target artery origin) |

| 3 | Total length of target artery disease 1/3–2/3 (10–20 cm); CTO 3–10 cm (may include target artery origin, but not TP trunk) |

| 4 | Total length of target artery disease >2/3 length; CTO >1/3 (>10 cm) of length (may include target artery origin); any CTO of TP trunk |

Trifurcation involvement is defined by disease that include the origin of either the anteriortibial or tibioperoneal trunk.

The combined scores of the FP and IP segments can then be used to determine the GLASS stage using the table below:

| FP Grade | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| IP Grade | 0 | NA | I | I | II | III |

| 1 | I | I | II | II | III | |

| 2 | I | II | II | II | III | |

| 3 | II | II | II | III | III | |

| 4 | III | III | III | III | III |

Stage I: Average Complexity Disease: immediate technical failure <10% AND >70% 12-month LBP. Stage II: Intermediate Complexity Disease: immediate technical failure <20% AND 12-month LBP 50–70%. Stage III: High Complexity Disease: immediate technical failure >20%; OR <50% 12-month LBP.

For a more complete explanation of the The Global Limb Anatomic Staging System (GLASS), please see here.

The SVS Guidelines Mobile App has an easy-to-use GLASS Calculator. - Apple App Store - Android Google Play

The Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Concensus (TASC classification)

In 2000, a group of fourteen societies from North America and Europe representing a variety of disciplines including vascular surgery, internal medicine, interventional radiology, and cardiology convened to create a consensus in the classification and treatment of patients with peripheral artery disease (i.e. intermittend claudication, acute limb ischemia, and chronic limb ischemia).

The Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus (TASC) document focuses on individual arterial segments and classifies lesions into one of four large groups (TASC A through TASC D) according to the pattern of disease. Recommendations are then offered according to TASC Classification.

TASC A lesions are those that should have excellent results from endovascular management alone.

TASC B lesions are those that should have good results from endovascular management and endovascular interventions should be the first option offered to the patient.

TASC C lesions are those that have better long-term results with open surgical management. Endovascular techniques should be reserved for patients who are poor surgical candidates.

TASC D lesions are those that should be treated by open surgery.

Important caveats: - Developments in endovascular techniques and devices since the introduction of the TASC document have increased the role of endovascular surgery in treating TASC C and TASC D lesions.

- Many patients with CLTI present with multisegment disease thereby complicating the clinical decision-making usefulness of TASC recommendations. TASC is more reasonably useful for assessing lesion-specific device performance.

The consensus was updated in 2007 (TASC II) and included representatives from Australia, South Africa, and Japan.

Treatment

Treatment of CLTI includes conservative management and invasive intervention. Lifestyle modification is recommended and highly encouraged and includes smoking cessation, regular exercise, and a healthy diet to reduce cardiovascular risk factors.

Conservative management

Pharmacotherapy with antiplatelet agents and statins plays a large role in helping prevent the progression of CLTI. Antiplatelet agents – such as aspirin or clopidogrel, reduce the risk of blood clots, while statins control cholesterol levels and reduce the progression of atherosclerosis. In some instances, vasodilators, such as cilostazol, can be utilized to improve blood flow and relieve symptoms, especially in those individuals experiencing ischemic rest pain.

Invasive management

The mainstay of treatment modality in CLTI is revascularization with endovascular therapy, surgical bypass, or a combination of both.

Endovascular revascularization is the least invasive approach to opening narrowed or blocked arteries. Using real-time contrast-enhanced images, the surgeon can perform angioplasty (i.e. ballooning of stenosis) stenting, and/or atherectomy (i.e. device mediated removal of the intimal layer and atherosclerotic material).

A surgical bypass, or extra-anatomic bypass, is the surgical creation of a new path for blood around the area of vessel stenosis/occlusion. Conduits for bypass can be artificial (e.g. PTFE or dacron grafts) or natural (e.g. autogenous or cadaveric saphenous vein grafts). In severe cases where limb salvage is not possible or limb-threatening infection persists even after attempts at revascularization, amputation may be necessary to preserve overall health and quality of life.

In addition to conservative management and surgical intervention, appropriate wound care is an important aspect of CLTI treatment. Surgical wound debridement, infection control, offloading techniques, and daily specialized wound care are integral in promoting healing and preventing amputation.

It is important to note that CLTI is a chronic disease, and patients may require multiple interventions, be on lifelong aspirin/statin therapy, and require close follow-up with routine imaging surveillance for the entirety of their lifetime. Moreover, vascular surgeons work with a team of physicians from other specialties – including primary care, cardiology, podiatry, nephrology, and endocrinology – in order to ensure that patients with CLTI are appropriately optimized given their respective comorbidities to improve overall outcomes. This integrative physician network to help manage CLTI patients is important as patency rates of stents and bypasses can be severely limited by a patient’s underlying disease burdens from uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, renal insufficiency, and tobacco abuse.

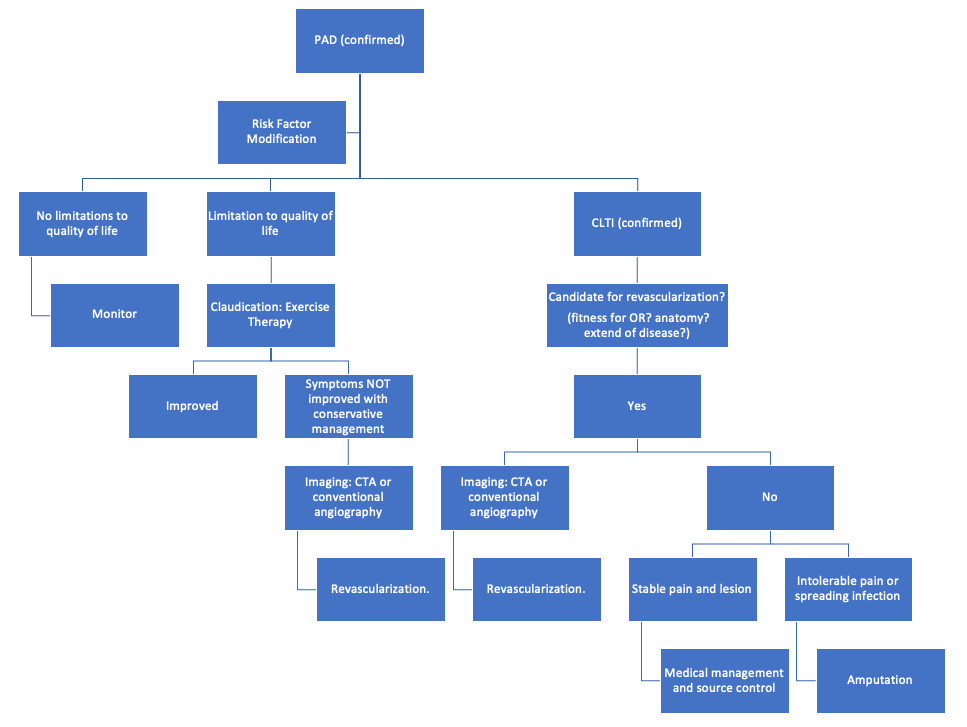

Below is a sample algorithm for treatment management of a patient with PAD that progresses to CLTI. Candidacy for revascularization indicates that the patient is able to tolerate anesthesia and has suitable anatomy - including possible targets for bypasses or the ability to traverse lesions endovascularly.

Here is an image demonstrating angioplasty, atherectomy, and placement of stents.

Here is an image demonstrating surgical or extra-anatomic bypass.

Outcomes

- Patients with CLTI have variable outcomes with regard to limb loss and overall mortality.

- Approximately 90% of all CLTI patients undergo a revascularization procedure (bypass or endovascular intervention) in their lifetime. (Conte et al. 2019b)

- For CLTI patients who do not undergo any revascularization, the natural history includes a 1-year major amputation and 1-year mortality rate of 22%. (Conte et al. 2019b)

- When looking at overall 1-year outcomes for all CLTI patients, 1-year amputation rates are at 15-20% and 1-year mortality is at 15-40%. (Conte et al. 2019b)

- Less than half of all CLTI patients (45%) will have both limbs after 1-year from initial time of diagnosis. These rates are even higher amongst the subset of CLTI patients who have diabetes. (Conte et al. 2019b)

- As the diagnosis of CLTI carries a high risk of mortality and morbidity even with vascular intervention to improve blood flow, there is a strong emphasis on preventing the progression of PAD to CLTI. (Conte et al. 2019b)

Surveillance

Medical Treatment Surveillance

- Patients with CLTI have variable outcomes with regard to limb loss and overall mortality.

- After revascularization procedures, Patients remain on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for 1-6 months.

- Through DAPT has been show to have increased bleeding risk, it may result in increased survival and reduced risk of amputation. (Conte et al. 2019b)

- There is not a clear benefit to the use of of cilostazol, a PDE inhibitor, after endovascular interventions for CLTI. (Conte et al. 2019b)

Endovascular Surveillance

- Early failure of endovascular procedures is common. As such, it is recommend that patients undergo duplex ultrasound surveillance and duplex guided interventions to prompt long-term patency. However, there are no set guidelines for how long and how frequently to perform surveillance.

- Recommended methods of surveillance include clinic visits, ankle-brachial indexes (ABIs), and duplex scans.

- Surveillance intervals can range from 3-6 months.

- Ultimately, there is no strong evidence of benefit of routine duplex surveillance after endovascular intervention of CLTI; however, patients with the characteristics below may benefit from duplex surveillance. (Conte et al. 2019b)

| Patient Risk Factors that may Prompt Duplex Surveillance |

|---|

| Multiple failed angioplasties and failed bypasses |

| Severe ischemia |

| Unresolved tissue loss |

| Poor Inflow |

| New Inflow Lesions |

Vein and Prosthetic Bypass Surveillance

Surveillance of vein grafts after bypass surgery may solely be clinical and may include the vascular laboratory as well. The SVS recommends a 2 year surveillance program postoperatively to detect new symptoms, monitor changes in ABIs, and monitor for stenotic lesions within graft or at surveillance sites.

- Duplex surveillance and intervention based on duplex findings lead to better patency rates of the vein graft.

- Though there are no set guidelines for frequency of surveillance. Many studies in the literature often perform surveillance 30 days postoperatively and at 3-6 months intervals.

- Ultimately, though duplex surveillance does result in better patency of vein grafts, there is no clear evidence that duplex surveillance for CLTI results in clinical benefits for patients.

Prosthetic bypasses are known to fail more frequently and more early compared to vein bypasses. Similar to vein bypassess, the SVS does not have hard recommendations for when to perform duplex surveillance.

- Many studies perform duplex at 30 days postoperatively and at 6 month intervals.

- Despite this, the duplex itself does not always always reliably detect intervenable lesions as it does in vein bypasses.

Teaching Case

Scenario

A 73-year-old male with a significant smoking history and medical history including 4 vessel coronary bypass 10 years ago, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes presents to clinic for pain in his lower extremities. He states that it is difficult for him to walk 3 blocks without having to stop. He locates the pain in his calves bilaterally.. He endorses he has experienced this pain for over 5 years. He mentions that he previously had a wound that took almost 3 months to heal. He denies presence of new sores or wounds. He had a right lower extremity angiogram 2 months ago that failed to recanalize the superficial femoral artery (SFA).

Exam

HEENT: No prior neck incisions, no lymphadenopathy.

Cardiac: Regular rate and rhythm (RRR), healed stereotomy scar.

Pulmonary: Clear to auscultation bilaterally, no increased work of breathing.

Abdominal: Soft, non-distended (ND), non-tender (NT)

Vascular/Extremities: Non-palpable lower extremity pulses and what appears to be a wound that is starting to form on the distal big toe of the right foot. He does have 2+ femoral pulses. On Doppler exam, he has monophasic dorsalis pedis (DP) and posterior tibial (PT) signals in his right lower extremity.

Imaging

Duplex Ultrasound: On duplex ultrasound, he has a long segment occlusion of the superficial femoral artery (SFA) and on CTA he has two-vessel run off to the right lower extremity with well-formed collateralization.

Discussion Points

However, we feel this chapter contains all the necessary information to answer the questions. If not, please let us know!

Please explain the pathophysiology of the patient’s lower extremity pain and non-healing wounds.

Please list the patient’s risk factors for Chronic Limb Threatening ischemia.

Explain why there is well-formed collateralization that was seen on CTA.

What next steps should be pursued to pursue treatment for the patient? Should the patient stop smoking?

What surgical treatment could be offered to this patient?

What additional imaging would help with surgical planning for the patient?

Key Articles

Beckman JA, Schneider PA, Conte MS. Advances in Revascularization for Peripheral Artery Disease: Revascularization in PAD. Circ Res. 2021;128(12):1885-1912. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318261.(Beckman, Schneider, and Conte 2021)

Berchiolli R, Bertagna G, Adami D, Canovaro F, Torri L, Troisi N. Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia and the Need for Revascularization. JCM. 2023;12(7):2682. doi:10.3390/jcm12072682.(Berchiolli et al. 2023)

Blanchette, Virginie, Malindu E. Fernando, Laura Shin, Vincent L. Rowe, Kenneth R. Ziegler, and David G. Armstrong. Evolution of WIfI: Expansion of WIfI Notation After Intervention. The International Journal of Lower Extremity Wounds, 2022. doi:10.1177/15347346221122860. (Blanchette et al. 2022)

Conte MS, Bradbury AW, Kolh P, et al. Global vascular guidelines on the management of chronic limb-threatening ischemia. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2019;69(6):3S-125S.e40. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2019.02.016.(Conte et al. 2019c)

Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135(12). doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000470.(Gerhard-Herman et al. 2017)

Mills JL, Conte MS, Armstrong DG, et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery Lower Extremity Threatened Limb Classification System: Risk stratification based on Wound, Ischemia, and foot Infection (WIfI). Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2014;59(1):220-234.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2013.08.003.(Mills et al. 2014)

Wijnand JGJ, Zarkowsky D, Wu B, van Haelst STW, Vonken EPA, Sorrentino TA, Pallister Z, Chung J, Mills JL, Teraa M, Verhaar MC, de Borst GJ, Conte MS. The Global Limb Anatomic Staging System (GLASS) for CLTI: Improving Inter-Observer Agreement. J Clin Med. 2021 Aug 4;10(16):3454. doi: 10.3390/jcm10163454. PMID: 34441757; PMCID: PMC8396876.(Wijnand et al. 2021)

Additional Resources

Audible Bleeding Content

- Audible Bleeding Exam Prep: CLTI Chapter

Gore Combat Manual

The Gore Medical Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Combat Manual is an informative and entertaining read intended as a vascular surgery crash course for medical students, residents, and fellows alike. Highly accessible with a thoughtfully determined level of detail, but lacking in learning activities (e.g. questions, videos, etc.), this resource is a wonderful complement to the APDVS eBook.

Please see pages 85-98.

Operative Footage

Developed by the Debakey Institute for Cardiovascular Education & Training at Houston Methodist. YouTube account required as video content is age-restricted. Please create and/or log in to your YouTube account to have access to the videos.