Hemodialysis Access

The pre/post questions are listed below. They are all multiple choice questions with a single right answer. To best guide your learning, we have hidden the answers in a collapsible menu. Before reading the chapter, we suggest giving the questions a try, noting your answers on a notepad. After reading the chapter, return to the questions, re-evaluate your answers, and then open the collapsible menu to read the correct answer and discussion. Do not fret if you have difficulty answering the questions before reading the chapter! By the end of the chapter, we are certain you will have covered the knowledge necessary to answer the questions. There will be a teaching case at the end of the chapter. This is another opportunity to exercise your new knowledge!

Pre/Post Questions

Case Based Questions

- A 35 year-old right-hand dominant female with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus presents to vascular surgery clinic after a referral from nephrology due to declining renal function. At the time of presentation the patient’s glomerular filtration rate is 23 mL/min/1.73 m2. According to her nephrologist, she does not require immediate renal replacement therapy, but she has no signs of improvement or recovery. She is expected to become hemodialysis-dependent in the next 6 months. Preoperative vein mapping was performed and identifed a 2.8 mm cephalic vein. What is her best option for hemodialysis?

Left forearm brachiocephalic arteriovenous graft

Left subclavian tunneled central venous catheter placement

Left radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula

Right forearm brachiocephalic arteriovenous graft

Right radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula

- A 21 year-old male who is a bodybuilder, is admitted to the intensive care unit with a significant crush injury following a motor vehicle collision. He has rhabdomyolysis and hyperkalemia that requires emergent hemodialysis. What is the most appropriate option for hemodialysis access?

Non-tunneled left internal jugular catheter

Tunneled left femoral catheter

Non-tunneled right internal jugular catheter

Tunneled right subclavian catheter

Non-tunneled femoral catheter

- A 60 year-old male with an upper arm arteriovenous fistula (AVF) presents for follow-up. Dialysis center reports prolonged bleeding.. Physical examination reveals a pulsatile AVF and a high-pitched systolic bruit best heard over the outflow vein. What diagnostic test should be performed next to confirm the suspected diagnosis?

Hemodialysis duplex

Computer tomography angiography

Right heart catheterization

Fistulogram

Magnetic resonance angiography

- A 58-year old female with a brachiocephalic arteriovenous fistula (AVF) presents with decreased dialysis efficiency and clots upon cannulation at dialysis. On examination, there is a weak thrill and an absent bruit over the AVF. What is the most likely cause?

Improper needle placement

High-output heart failure

AVF thrombosis

Venous outflow stenosis

Central venous stenosis

- A 62-year-old male on hemodialysis presents with hand pain, coldness, and pallor at rest which worsens during dialysis sessions. The pain becomes so severe that he often cannot complete the entire dialysis session. On examination, compression of the arteriovenous fistula (AVF) mildly improves hand perfusion and partially relieves his symptoms. What is the best management strategy?

Percutaneous angioplasty

Revision using distal inflow (RUDI)

AVF ligation

Observation

- A 37-year-old female with a history of end-stage renal disease presents with an upper arm arteriovenous graft (AVG) that was placed six months ago. Over the past three days, she has experienced increasing redness, warmth, and tenderness around the graft site, along with a general feeling of malaise. On physical examination, she is febrile, tachycardic, tachypneic, and appears flushed. Examination of the AVG reveals fluctuance and purulent drainage. What is the most appropriate management?

Start intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics

Surgical debridement, AVG removal and intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics

Percutaneous drainage of the abscess

Graft excision and immediate replacement

- A 55-year-old person is being evaluated for the creation of a left radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula (AVF). An Allen test is performed to assess the suitability of his radial artery for use in the fistula. Which of the following indicates a negative (normal) Allen test, suggesting adequate collateral circulation through the ulnar artery?

Delayed color return to the hand after releasing ulnar artery compression

Immediate color return to the hand after releasing ulnar artery compression

Absence of change in hand coloration during the test

Persistent pallor of the hand after releasing ulnar artery compression

Introduction

Renal failure encompasses a range of conditions, including acute kidney injury (AKI), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Renal failure is a condition marked by impaired water and electrolyte homeostasis, acid-base imbalance, loss of endocrine kidney functions, and hematologic accumulation of toxic nitrogenous end-products with associated signs and symptoms (Table 1). CKD, affecting over 10% of the global population, is characterized by a gradual loss of kidney function over time, often progressing to ESRD if untreated. Hemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD), are the primary modality of life-sustaining renal replacement therapy in both acute and chronic cases. Both dialysis methods work by using a semipermeable membrane to separate waste products and excess substances from the blood. These therapies can serve as a bridge to kidney transplantation or as a long-term treatment solution.

| FUNCTIONS OF THE KIDNEY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF RENAL FAILURE |

|---|

| Function |

| Salt, water, and acid-base balance |

| Water balance |

| Sodium balance |

| Potassium balance |

| Bicarbonate balance |

| Magnesium balance |

| Phosphate balance |

| Extraction of nitrogenous end products |

| Urea, Creatinine, Uric acid, Amines, Guanidine derivatives |

| Endocrine-metabolic |

| Conversion of vitamin D to active metabolite |

| Production of erythropoietin |

| Renin |

Table 1: Functions of the kidney and pathophysiology of renal failure.

ESRD disproportionately affects historically disadvantaged populations. In the U.S., the incidence of ESRD among Black individuals is nearly four times that of White individuals. The rates are also higher among Native American and Hispanic populations. (Francis et al. 2024) (“Annual Data Report,” n.d.) (“Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States - NIDDK,” n.d.) The incidence of ESRD also has significant regional variability, reflecting disparities in healthcare access and risk factor distribution. (“Annual Data Report,” n.d.) (“Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States - NIDDK,” n.d.) CKD is slightly more common in women, but men are more likely to experience worse outcomes and progress to ESRD. (“Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States - NIDDK,” n.d.)

In the United States, nearly 808,000 people live with ESRD, with 69% currently undergoing dialysis and 31% having had a kidney transplant. (“Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States - NIDDK,” n.d.) The rising burden of CKD and ESRD has been driven by the aging population and the increasing prevalence of diabetes and hypertension, two of the leading risk factors for kidney failure. (“Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States - NIDDK,” n.d.) Other key risk factors include advancing age, cardiovascular disease, and obesity. (Francis et al. 2024) (Johansen et al. 2024a)

This growing disease burden imposes significant economic and healthcare challenges. The high prevalence of ESRD is associated with increases in healthcare costs, driven by the use of long-term catheters and hospitalizations for dialysis access-related complications. (Francis et al. 2024) (“Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States - NIDDK,” n.d.) (Johansen et al. 2024a) Globally, access to kidney replacement therapy remains unequal, with low- and middle-income countries accounting for a disproportionately small percentage of treated patients despite a higher need. (Francis et al. 2024)

These disparities underscore the essential role of vascular surgeons in managing dialysis access. Accordingly, establishing a dialysis life plan that balances reliable access for effective treatment, sustains patients’ quality of life, and optimizes healthcare resource allocation is essential. The dialysis life plan is a proactive, individualized strategy developed through multidisciplinary collaboration, typically involving multiple healthcare providers including nephrologists, vascular surgeons, and the patient. It outlines the anticipated sequence of dialysis modalities and access types, aiming to preserve future access sites and minimize complications. Early planning can reduce the reliance on catheters, lower infection rates, and improve long-term outcomes. For patients with limited vascular options or complex comorbidities, this approach also helps prioritize access choices that align with their clinical trajectory and personal preferences. As the prevalence of ESRD continues to rise, widespread implementation of dialysis life plans is critical to delivering equitable, sustainable, and patient-centered care.

Peritoneal Dialysis

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a type of renal replacement therapy that uses the patient’s peritoneal membrane as a filter to remove waste products and excess fluid from the body. For access, a tunneled intraperitoneal catheter is surgically placed in the pelvis. Dialysis is typically initiated 2–4 weeks after catheter placement to allow for healing and reduce the risk of infection. During a PD session, approximately 1 liter of sterile dialysate is infused into the peritoneal cavity through the catheter. The fluid remains in the cavity for a prescribed dwell time, during which waste products and excess fluids diffuse from the blood vessels in the peritoneal membrane into the dialysate. The used dialysate is then drained from the cavity, completing the exchange process.

PD enables patients to perform dialysis treatments at home, at work, or while traveling, providing greater autonomy and flexibility compared to in-center hemodialysis. Many patients prefer to conduct PD overnight using automated cyclers. However, PD requires comprehensive training in dialysis techniques, strict adherence to sterile procedures to prevent infections, and several daily exchanges of dialysate. Therefore, this modality is generally recommended for patients who are highly motivated, capable of managing the technical aspects of PD, and have a strong support system.

PD is often considered superior in preserving residual renal function due to its more gradual fluid and solute removal, which creates fewer fluctuations in volume and osmotic load compared HD. (Alrowiyti and Bargman 2023) By avoiding rapid changes in circulating body volume and osmolality, PD helps maintain a steadier glomerular capillary pressure and more consistent glomerular filtration. This lowers the risk of renal ischemia and transient hemodynamic instability.

Despite these benefits, certain clinical scenarios present relative contraindications, such as:

Recent abdominal or chest surgery where the diaphragm or abdominal wall has been violated (risk of fluid leaks and infections)

Severe respiratory failure (elevated intra-abdominal pressure can compromise breathing)

Life-threatening hyperkalemia (PD may not correct potassium levels rapidly enough)

Fecal or fungal peritonitis (increased risk of contamination)

Absolute contraindication: Patient history of Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HPIEC), a surgical procedure that destroys the peritoneal membrane to prevent cancer spread (Without a functional peritoneal membrane, you cannot perform PD).

Having considered these constraints, the next step is to examine the potential complications of PD. PD complications are usually related to the catheter itself:

Catheter Occlusion: Secondary to a kink in the tubing, fibrinous deposits within the catheter lumen, or stool burden causing mechanical obstruction of the catheter as it transverses the peritoneum.

Catheter-Related Peritonitis: Presents with abdominal pain, tenderness, fever, and cloudy dialysate fluid. Analysis of the dialysate fluid often reveals a white blood cell count greater than 100 cells/µL (Normal < 8 cells/µL). Management usually requires intraperitoneal antibiotic treatment and possible catheter removal.

Over time, patients may transition from PD to HD due to a further decline in residual kidney function or changes in the peritoneal membrane, often secondary to recurrent peritonitis, which reduces the effectiveness of PD.

Hemodialysis

Introduction

HD is the most common modality of renal replacement therapy for patients with renal failure. The dialysis process involves withdrawing blood through a high-flow vascular access. Options include, a central venous catheter (CVC), arteriovenous fistula (AVF), or arteriovenous graft (AVG). This connection between the high-pressure arterial system and low-pressure venous system increases venous blood flow, resulting in venous dilation and easy cannulation for treatment. High flow rates are necessary to ensure the efficient removal of waste products and excess fluids, as well as to maintain adequate clearance of toxins during the limited time of each dialysis session. This blood is circulated through a dialysis machine, where it undergoes purification through diffusion, filtration, and convection to remove waste products and correct electrolyte abnormalities before being returned to the patient via the same high-flow access. Standard intravenous lines are inadequate for this purpose, as they cannot sustain the required high flow rates of at least 300-500 mL/min needed for hemodialysis.(“Peripheral IV Catheter Chart,” n.d.) Direct access of an artery or a vein is also unsuitable for HD because they cannot sustain the repeated punctures required for dialysis sessions and similarly do not provide the high flow rates needed for effective treatment. Vascular surgeons must ensure proper vascular access creation and maintenance for successful dialysis outcomes.

Vascular Access

Indications

The decision to initiate HD is a multifaceted process that requires consideration of clinical factors and patient needs. HD needs can be expected and chronic or acute and urgent. HD most commonly comes to mind when discussing therapies for patients with renal failure. The 2019 Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guidelines recommend that patients with CKD stage 4 (GFR, 30 mL/min/1.73 m2) be counseled on renal failure and treatment options 13. Early counseling allows patients and their families to understand treatment outcomes and prepare for decisions about renal replacement therapy. HD is life-sustaining in patients with eGFR < 10-15 mL/min/1.73 m². HD initiation should not be based solely on kidney function, but rather on symptoms of renal failure, such as pruritus, acid-base or electrolyte abnormalities, volume or blood pressure dysregulation, and progressive deterioration in clinical status. (Lok et al. 2020a) In addition to chronic conditions, there are also acute indications for hemodialysis.

Refractory metabolic acidosis: Persistent metabolic acidosis with a pH less than 7.15, despite appropriate medical treatment, requires hemodialysis to restore acid-base balance, particularly through bicarbonate. (Kraut and Madias 2010)

Electrolyte imbalances: Life-threatening electrolyte disturbances, such as hyperkalemia (potassium > 6.0 - 6.5 mmol/L) that do not respond to medical intervention, represent an immediate need for dialysis to prevent cardiac complications and arrhythmia. (Charytan and Goldfarb 2000)

Ingestion and intoxication: Dialysis may be indicated in cases of certain toxic or medication ingestions where rapid removal of the toxin is necessary to prevent severe complications or death. Toxic subtances/medications include: Isoniazid, isopropyl alcohol, salicylates, theophylline, uremia, methanol, metformin, barbiturates, lithium, ethanol, ethylene glycol, Depakote (divalproex sodium), and dabigatran. (King, Kern, and Jaar 2019)

Volume overload: Fluid overload unresponsive to diuretics, particularly if it leads to respiratory compromise or exacerbates congestive heart failure, necessitates dialysis for volume control.

Symptomatic uremia: Symptoms of uremia, including nausea, vomiting, pruritus, altered mental status/encephalopathy, or pericarditis are indicative of accumulating toxins that the failing kidneys cannot clear.

The AEIOU mnemonic can be used to recall the urgent initiations for dialysis:

Acidosis, Electrolyte abnormality, Intoxication, volume Overload, and Uremia (“AEIOU”).

Creating vascular access for HD is generally avoided in patients with severe hemodynamic instability, uncontrolled active bleeding, or advanced malignancies where life expectancy is limited and dialysis is unlikely to improve quality of life. (Lok et al. 2020a) In these cases, palliative care focused on symptom management and comfort is often more appropriate. Decisions regarding vascular access creation for HD should involve a multidisciplinary team and an individualized approach to ensure that treatment aligns with the patient’s clinical status and goals of care.

Access Type

The decision to create vascular access for HD, as well as the type of access chosen, is guided by several interdependent patient-specific factors in the dialysis life plan. HD access sites are limited and dictated by the clinical scenario, so careful planning is essential to preserve options and ensure the best long-term outcomes for patients. A comprehensive access plan considers the combination of the timing and urgency of dialysis initiation by using all access forms including catheters, fistulas, and grafts. In Table 2, we explore these considerations. Briefly, AVFs, which are created using the patient’s own vein and artery, are considered the gold standard for long-term HD access due to their durability and lower infection risk. (Lok et al. 2020a) They require early planning, created 4-6 months before anticipated dialysis, and usually takes the fistula 6-8 weeks to mature. AVGs, made using synthetic materials or donor vessels, provide a good alternative for patients whose veins are unsuitable for an AVF. They also require early planning but mature faster by endothelializing in 2-4 weeks. Early access grafts can be used as early as the following day.

The progression from temporary to permanent access often begins with catheter-based access. Temporary access is common, with roughly 80% of patients starting HD using this method. (“2019 Annual Data Report - USRDS - NIDDK,” n.d.) They are typically used when dialysis is needed in those with limited life expectancies, urgently when there is no time to create an AVF or AVG, or as a bridge to permanent access intervention. (Lok et al. 2020a) They are most often used when waiting for an AVF to mature. CVCs, while providing immediate cannulation access after placement, are meant for short-term use due to a higher risk of infection and complications. Early access placement has been shown to decrease the risk of sepsis and death when compared to late access creation by reducing the use of CVCs. (Oliver et al. 2004) Having the same practitioner or a coordinated team handle both catheter placement and subsequent permanent access ensures better continuity of care.

| Access type | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AVF | AVG | CVC | |

| Type | Autologous | Synthetic | Synthetic |

| Material | Patient’s own artery and vein. The minimum size should be >2mm in the forearm and >3mm in the upper arm. | Cryopreserved donor vessel or PTFE, Dacron | Medical-grade polymers (polyurethane, silicone) |

| Description | An AVF is a surgically created connection between an artery and an autologous vein. | An AVG is a surgically created connection between an artery and a vein using a prosthetic conduit. | Temporary: Catheters placed directly into a central vein. Tunneled CVCs: Catheters placed under the skin and tunneled to a central vein. |

| Duration of use/ permanency | Gold standard for long-term access. | Long-term. | Temporary CVC: Short-term, 2-3 weeks, immediate use, high possibility of dislodging or infection. Tunneled CVC: Medium-term access while awaiting maturation of permanent option (e.g., AVF/G). |

| Access timing | Early access: Placed through planned surgery 4-6 months before anticipated HD need. | Early access: Placed via planned surgery 4-6 months before anticipated HD need. | Late access: Placement for unanticipated dialysis for immediate use. |

| Maturation time | 6-8 weeks | 2-4 weeks | N/A |

| Placement | UE > LE. Nondominant arm > Dominant arm | UE > LE. Nondominant arm > Dominant arm | IJV or FV. SV as a last resort. RIJV > LIJV |

Table 2: Considerations for the various types of vascular access options. (AVF, arteriovenous fistula; AVG, arteriovenous graft; CVC, central venous catheter; PTFE, polytetrafluoroethylene; UE, upper extremity; LE, lower extremity; IJV, internal jugular vein; FV, femoral vein; SV, subclavian vein)

Tunneled CVC indications:

Tunneled CVCs are used for both short-term and intermediate-term access. They serve as a bridge therapy for more permanent access in patients requiring long-term dialysis or in patients who have expected dialysis durations of < 1 year or life expectancy of < 1-2 years. They are also used for continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) in ICU settings or when AVF/G is contraindicated, such as in heart failure. Due to high infection risk, tunneled CVCs are generally not recommended for outpatient use.

The Rule of 6s to recall the criteria that define a mature AVF

Flow rate > 600 mL/min, Vessel diameter > 6 mm, Cannulation site depth < 6 mm from the skin surface, and Cannulation segment length > 6 cm, > 6 weeks post-op.

Access Location

The choice of HD access location involves a systematic approach, balancing anatomical considerations, patient-specific factors, and the need to preserve future access options. Upper extremity access is prioritized due to its lower risk of complications and better long-term outcomes compared to lower extremity access. (Lok et al. 2020a) The initial focus is typically on distal forearm access, as it allows for the preservation of proximal options. A radiocephalic or snuffbox AVF, which connects the distal radial artery to the cephalic vein, is preferred when the vessels are suitable, as it minimizes dissection and offers low complication rates. When forearm options are not viable, attention shifts to upper arm access. The brachiocephalic AVF, connecting the brachial artery to the cephalic vein, is a preferred option for achieving high flow rates. If the cephalic vein is unsuitable due to depth or position, a basilic vein transposition can be performed, requiring mobilization of the vein to a superficial position for easier cannulation.

When both the cephalic and basilic veins are inadequate, alternative autogenous veins, such as the brachial, femoral, or saphenous, may be used for transposition or translocation. These approaches require extensive dissection and are associated with increased morbidity. A common point of debate is whether to use forearm prosthetic access as a temporary bridge or proceed directly to upper arm autogenous AVF creation. Forearm prosthetic grafts are typically viewed as interim solutions, with the goal of transitioning to an upper arm autogenous AVF when feasible. This decision depends on the patient’s vascular anatomy, long-term dialysis requirements, and overall health as part of their end-stage renal disease (ESRD) life plan.

Upper extremity access can be further pursued using prosthetic loop grafts. A straight forearm graft may connect the radial artery to the proximal cephalic vein, while loop configurations may be created between the brachial artery and cephalic vein, among other vessels. The loop design offers a larger surface area for cannulation and may improve ease of access. In rare cases, a “necklace” graft, linking the axillary artery to the ipsilateral or contralateral axillary vein, is employed when conventional upper extremity options are exhausted.

Lower extremity access is reserved as a final option. This typically involves using the femoral or saphenous vein, either transposed or incorporated into a loop graft with the femoral artery. Patients considered for lower extremity access must be carefully screened for peripheral arterial disease (PAD), as these configurations are associated with higher morbidity and reduced long-term patency.

The use of the basilic vein in AV access usually requires transposition because it is located deep and medial.

After selecting the appropriate access location, the next critical step involves determining the optimal approach for access creation. Staged procedures, particularly in cases where vein maturity and long-term suitability are uncertain, offer a strategic pathway to optimize outcomes. These approaches enable better evaluation of vein quality, minimize unnecessary dissections, and increase the likelihood of creating durable, functional vascular access (Table 3)

| Description | Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-Stage | Single surgery. | Requires only one surgical session, reducing overall procedure time and anesthesia exposure. | If the access fails to mature, the patient endures extensive dissection with no benefit, potentially discouraging future attempts. |

| Two-Stage | First stage creates the anastomosis; second stage, performed after 4-6 weeks, mobilizes vein. | Allows assessment of vein maturity before major dissection, reducing unnecessary surgeries. | Requires two surgeries, leading to increased overall procedure time and anesthesia exposure. |

Table 3: Advantages and disadvantages of staged access creation

Hemodynamic Considerations

Understanding the principles of fluid hemodynamics in dialysis access is key, including pressure gradients, flow, and resistance. Pressure gradients drive the movement of blood through vessels, flow represents the volume of blood passing through a vessel over time, and resistance is the force opposing this flow, influenced by vessel diameter and length. Understanding these concepts is important because manipulating vascular access impacts systemic circulation, which can alter cardiac output, increase strain on the heart, and influence overall hemodynamic stability.

Cardiac output: After AVF creation, increased blood flow through the fistula leads to a rise in cardiac output as the heart meets the increased demand for greater perfusion. The low-resistance AVF pathway allows more blood to flow, requiring the heart to pump harder to maintain systemic circulation.

Heart strain: The increased flow through the AVF results in greater venous return, which can place additional strain on the heart, potentially exacerbating heart failure in susceptible patients.

Hemodynamic stability: AVF creation reduces systemic vascular resistance by providing a low-resistance pathway, which can decrease blood pressure. This drop requires monitoring and adjustment of antihypertensive medications to prevent complications like hypotension.

Given the finite number of viable sites, nearly every fistula is placed as distally as possible to preserve future vascular access sites for revisions or new fistulas. Distal placement also helps maintain blood flow to proximal branches by increasing the length of the artery before blood can siphoned into the AVF/G, which naturally adds resistance. Increased resistance limits the amount of blood diverted into the fistula, helping to ensure adequate distal perfusion. Additionally, keeping the arteriotomy length small (4-6 mm) increases resistance, which regulates the volume of blood entering the fistula and prevents excessive preferential flow. This approach reduces the risk of complications like steal syndrome and optimizes long-term fistula function.

Poiseuille’s law and resistance in dialysis access:

Poiseuille’s Law, expressed as 𝑅 =8𝜂𝐿/𝜋𝑟4, reveals the relationship between vessel diameter, length, and flow resistance. The radius (r) of a vessel has the most profound effect—resistance is inversely proportional to the fourth power of the radius, meaning small decreases in radius greatly increase resistance. Halving the vessel radius results in a 16-fold increase, highlighting why small changes in arteriotomy length can have dramatic effects on flow dynamics. Similarly, increasing the length (L) of the vessel directly increases resistance.

Resistance and AVGs:

In AVGs, the fixed diameter of the synthetic graft may reduce the risk of steal syndrome.

Steal Syndrome and anastomosis location:

In upper extremity AVFs, the highest risk of steal occurs when the anastomosis is located on the brachial artery due to increased diameters (and thus flows), and a more proximal location (thereby affecting a larger vascular bed, i.e. the radial artery, ulnar artery, and collaterals).

The type of anastomosis used also has significant implications for venous pressure and flow. In an end-to-end anastomosis, the artery is connected to the end of a vein, exposing the vein to full arterial pressure without any distribution or regulation. This results in excessive pressure, increasing the likelihood of venous hypertension and failure of the access site. In contrast, an end-to-side anastomosis connects the end of an artery to the side of a vein, allowing arterial blood to enter in a more regulated manner. This configuration essentially dilutes arterial flow within the vein, enabling it to handle the mixed flow by carrying venous blood alongside arterial inflow rather than receiving the full brunt of arterial pressure alone. The controlled entry of arterial blood helps prevent overwhelming the venous system, allowing the fistula to mature and thicken, improving its ability to handle increased flow and enhancing long-term patency.

Emerging Technologies

Percutaneous AVF Creation

The FDA has approved two endovascular devices (Ellipsys Endo AVF and WavelineQ Endo AVF) for AVF creation. (Shahverdyan et al. 2020) These systems involve percutaneous access of a vein and artery, followed by either thermal induction or radiofrequency ablation to create the fistula. These procedures can be performed using ultrasound guidance alone or with fluoroscopy, offering newer options for minimally invasive treatment and in patients who are not ideal candidates for open surgery (of note, open radiocephalic AVF creation is inidcated over percutaneous technologies if feasible).

HeRO Graft

When conventional treatments have been exhausted, what options remain? How should you manage patients with central venous stenosis or occlusion who have a CVC in place or have the ability to place a wire into the central venous circulation? Temporary lines or lower extremity access might be alternatives, but are there other viable solutions? In these challenging situations, the hemodialysis reliable outflow (HeRO) graft may be considered.

The HeRO graft consists of two main components that transition from one to the other along its length: a venous outflow component and an arterial inflow component. The arterial inflow component is tunneled subcutaneously and anastomosed to an artery, while the venous outflow component is placed into the central venous circulation, bypassing any stenosis or occlusion, similar to a CVC. This configuration provides an immediate, reliable, and permanent site for cannulation and ensures adequate flow dynamics. However, this approach is generally reserved as a last resort due to its association with a high complication rate and relatively low patency. (Al Shakarchi et al. 2015)

Diagnostics and Imaging

A comprehensive pre-operative assessment for successful vascular access creation involves a detailed history and physical examination, supplemented with diagnostic imaging as needed. The primary goal of the preoperative assessment is to identify vessels capable of supporting the high blood flow required for dialysis and identifying pre-existing lesions that can be corrected before access creation.

History

Patient history is among the most important factors for access determination. A comprehensive understanding of the patient’s medical history, current indications for HD, and overall care goals should guide the decision-making process. When assessing a patient for HD access, particular attention should be paid to the following elements:

Comorbidities: Assess for the presence of diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, and obesity, as these conditions are associated with lower fistula patency rates. (Lok et al. 2006) (Smith, Gohil, and Chetter 2012a)

History of trauma and surgeries: Obtain detailed information regarding any history of trauma or prior surgeries, especially involving the chest, arms, or central vasculature. Previous vascular procedures or significant injuries may impact available access options.

Previous vascular access: Document any prior HD or central venous access, including its type, location, duration, and any complications encountered. It is particularly important to assess if an existing AVF is functional and for potential central venous stenosis (CVS). Understanding the history of previous access helps make informed decisions regarding the best site for new access.

Dominant extremity: Establish the patient’s dominant arm. HD access is typically performed on the non-dominant arm to allow the patient greater functionality during dialysis sessions. However, if vascular abnormalities exist in the non-dominant arm, the dominant extremity may need to be considered.

Implanted devices: Avoid placing HD access on the same side as transvenous pacemakers or other implanted devices to prevent complications such as arm edema and venous thrombosis

Smoking status: Determine if the patient smokes, as smoking is linked to higher failure rates of AV access. (Wetzig, Gough, and Furnival 1985) Patients should be counseled on smoking cessation.

Lifestyle considerations: Understand the patient’s lifestyle and ability to adhere to HD. Hemodialysis requires a significant time commitment, and alternative access methods, such as PD, may be more suitable for patients seeking flexibility.

Physical Examination

A thorough physical examination should determine the suitability of potential vascular access sites. This should include an assessment of previous access sites, current AVFs, and the condition of the arterial and venous systems.

Arterial System

- Examination of arterial pulses: Palpate the brachial, radial, ulnar, and axillary pulses bilaterally. Assess for pulse strength, compressibility, and symmetry between the arms. Utilize a handheld bidirectional Doppler if pulses are not clearly palpable, grading them as normal (2+), diminished (1+), or absent (0).

- Differential blood pressure measurement: Measure the blood pressure in both the upper extremities. A difference of less than 10 mmHg is considered normal. Differences of 10 to 20 mmHg may be marginal, while differences greater than 20 mmHg are indicative of potential arterial stenosis and require further evaluation. (Lok et al. 2020b) Significant stenosis can impact the success of AV access and increase the risk of hand ischemia after access placement.

- Arterial adequacy: Factors such as advanced age, diabetes, hypertension, and arterial occlusive disease can compromise arterial supply. (Lazarides 2002) Calcified lesions in peripheral arteries are common in patients with these comorbidities and can complicate anastomosis, hinder fistula maturation, or increase the risk of hand ischemia.

- Allen test: The Allen test is a method used to evaluate the patency of the palmar arch, which is crucial to ensure adequate collateral circulation before HD access creation. To perform this test, the patient is asked to clench their fist tightly. The examiner then compresses both the radial and ulnar arteries. The patient is instructed to open their hand, which should appear blanched. The examiner releases pressure on the ulnar artery while keeping the radial artery compressed. If normal color returns to the hand within 5-7 seconds, it indicates a patent ulnar artery. (Jarvis et al. 2000) This process can then be repeated for the radial artery to confirm its patency. The modified Allen test is based on the same principles and uses the aid of a pulse oximeter. A pulse oximeter is placed on the patient’s index finger, and both the radial and ulnar arteries are compressed until the pulse waveform disappears, confirming adequate compression. Upon release of the ulnar artery, if the pulse waveform returns, the test is negative, indicating a patent ulnar artery. Repeat the process with the radial artery to ensure collateral circulation is sufficient. (Lok et al. 2020b) (Paul and Feeney 2003)

Venous System

The venous system is often prone to complications that can affect successful access due to the frequency of iatrogenic venous injuries, particularly because of the common use of arm veins for IV placements, blood draws, and other interventions that can cause trauma to these vessels. (Lee et al. 2012)

Depth and distensibility: Assess vein distensibility by inflating a blood pressure cuff or using a tourniquet above the veins to demonstrate that the vein can dilate to at least 50% of its resting internal diameter. (Smith, Gohil, and Chetter 2012b) (Malovrh 2002) (Lockhart et al. 2006) This step helps identify suitable veins for creating vascular access.

Evaluation of CVS and outflow obstruction: Examine the chest, breast, and upper arms for signs of swelling, collateral veins, or significant differences in extremity diameter, as these may indicate CVS or occlusion. (Tessitore et al. 2014) For further explanation, please refer to the Surveillance section.

Previous Access

It is also important to assess for any previous vascular sites.

Examine for scars: Look for scars that indicate prior access, including both central and peripheral sites. Note the location and compare the findings to the contralateral limb.

Identify the type of access: Determine the type of previous access. If there is a scar present on the anterior surface of the forearm, this is most likely a radial-cephalic AVF/G. If there is a scar on the anterior surface of the upper arm, this is most likely a brachial-cephalic or basilic AVF/G.

Assess patency: Check the patency of the existing fistula. A palpable thrill or audible bruit indicates patency for AVFs.

Evaluation of CVS and outflow obstruction: As described above, examine the chest and upper arms for signs of swelling. In addition, a pulsatile AVF/G may indicate venous stenosis, which would require further imaging. For further explanation, please refer to Surveillance.

Diagnostic Imaging Studies

Although vascular mapping with duplex US is not universally performed before AV access creation, it can help avoid potential problems by detecting pre-existing lesions before access. Further evaluation with diagnostic imaging is warranted when abnormalities are detected during the physical examination. These include but are not limited to, absent or reduced pulses, an abnormal Allen test, or significant differences in arm pressures. Additional studies such as a wrist brachial index, direct arterial ultrasound, angiography or venography may be neccessary before or after AV access creation. The 2019 KDOQI guidelines recommend using vascular imaging in complex cases, such as those involving obesity, multiple comorbidities with suspected vascular lesions, and previous failed accesses. (Lok et al. 2020c) Imaging often alters the plan for AV access when determined based solely on physical examination findings. (Nursal et al. 2006) (Smith et al. 2011) These imaging studies can assess the suitability of vessels for hemodialysis access while also minimizing the risk of procedural complications.

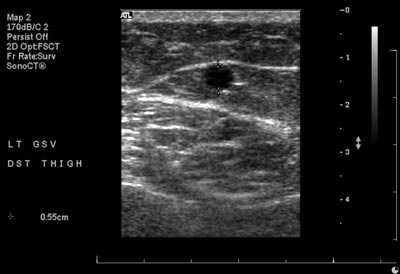

Duplex ultrasound (US)

This is the first-line imaging modality for evaluating vascular access. It allows for vein mapping, which involves assessing the venous anatomy at multiple points along the vessel to determine vein condition, diameter, depth, and tortuosity. It is non-invasive, widely accessible, low cost, and does not require intravenous contrast, which is important for pre-dialysis patients who may be at risk of nephrotoxicity. Duplex US has a high degree of concordance with angiography while avoiding the risks associated with invasive procedures. (Georgiadis et al. 2015) However, duplex US has limitations, such as the inability to visualize central veins adequately.

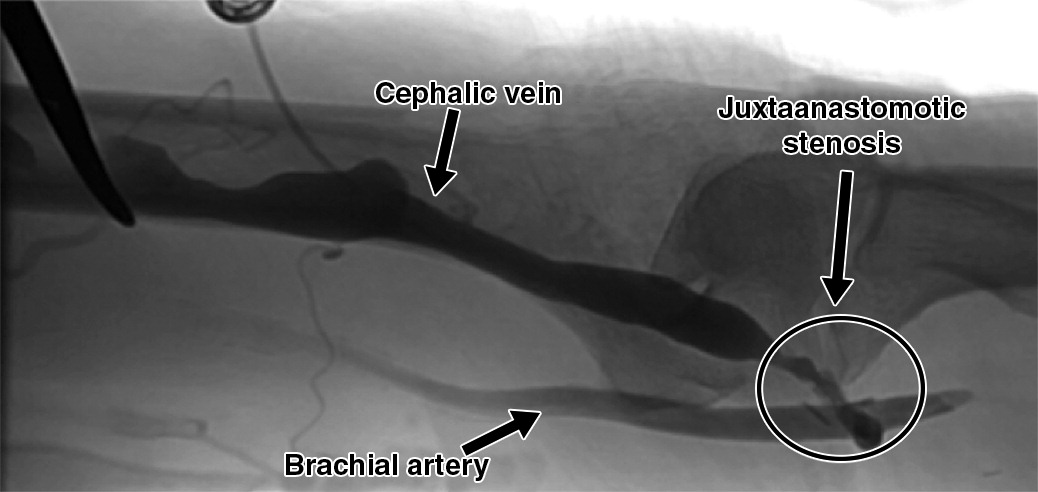

Angiography

Angiography, a fistulogram, remains the gold standard for diagnosing and treating vascular abnormalities. (Lok et al. 2020c) Angiography is indicated for venous mapping when duplex US reveals significant but unclear abnormalities or when high-quality ultrasound is unavailable. This imaging modality provides excellent visualization of both peripheral and central venous vasculature, allowing for a precise assessment of vessel anatomy, including tortuosity and configuration, which is particularly valuable for surgical planning in complex cases. It can also be performed using a tourniquet to create venous distention, approximating the size of an arterialized vein in a mature AVF.

Vessel size in HD access:

Vessel size can be evaluated by US or angiography. While there is no generally recognized size for access, studies suggest a minimum vein and artery diameter of 2 mm for access creation. (Lok et al. 2020c) (Schmidli et al. 2018a) Many institutions aim for a minimum vein diameter of 3 mm and artery diameter of 2 mm.

N.B. Size discrepancies between pre-operative vein mapping on on the table vein mapping occur. Always perform an ultrasound study in the operating room to assess vein quality and diameter.

Surveillance

Follow-Up

When AV access fails in a patient dependent on HD, it can lead to disruptions in dialysis treatment, including missed or insufficient sessions. This not only poses significant risks to the patient’s health, but may also necessitate hospitalization and the use of temporary CVCs, which are associated with higher infection rates and other complications. These outcomes diminish the patient’s quality of life and place a financial burden on the healthcare system due to increased treatment costs and resource utilization. Early evaluation and ongoing surveillance are essential to detect and address issues before they lead to failure. Regular monitoring helps improve AVF maturation rates, extends their functional longevity, and minimizes patient morbidity.

History is a good first step when evaluating AV access after creation. Assess for symptoms of central venous stenosis (CVS) including prolonged bleeding, difficulty cannulating, and swelling. Assess for ischemic symptoms like pain during dialysis sessions. In conjunction with a thorough history, physical examination is a simple and cost-effective method to detect common issues with AVFs. (Luis Coentrão and Turmel-Rodrigues 2013b) Combining physical examination with Doppler US provides the highest sensitivity and specificity for identifying problems. (Prabhakaran et al. 2023b) Any abnormalities detected during the physical exam should prompt referral for advanced diagnostic testing to confirm the findings and guide appropriate intervention. Key elements of the physical examination include:

Inspection: Identify the type of fistula and anatomy by noting location, scars, and configuration. Inspect the extremity and chest wall, comparing to the contralateral side. Assess for CVS by looking for facial plethora, respiratory distress, and edema or swelling in the upper extremity, neck, chest and face. The patient may also develop dilated and tortuous collateral veins over the ipsilateral arm, neck, and chest and aneurysmal dilation of the AV access. Assess for ischemic signs like hand coolness, loss of distal pulses, and diminished sensation. Assess for signs of infection on the skin overlying the fistula. All ulcers should be extensively examined.

Pulse: Evaluate the pulse in the AVF When there is a downstream stenosis (toward the chest), blood flow is forced through a narrowed segment, creating elevated pressure on the upstream side. This extra pressure amplifies the pulse wave you feel when examining the access, leading to a distinctly strong or “hyperpulsatile” pulse. The greater the stenosis, the more pronounced this pulsatility because the fistula is essentially pushing blood against a tighter restriction. Conversely, if the AVF is completely thrombosed, there is no flow moving through it, so no pulse wave can be generated. The exam will reveal an absence of a pulse, reflecting no forward flow in the occluded access.

Thrill: A thrill represents the palpable vibration caused by the high-velocity flow in the AVF, especially near the arterial anastomosis where the pressure differential is greatest. In a healthy AVF, turbulent arterial blood rushing into the venous system creates this distinct buzzing sensation. When differentiating thrill characteristics in an AVF, consider where the stenosis lies along the flow pathway. If there is a stenosis in the venous outflow (“downstream” from the anastomosis), blood faces increased resistance as it exits the fistula, leading to higher pressure within the AVF and a stronger, more pulsatile thrill In contrast, when the stenosis is located in the arterial inflow (“upstream”), the volume of blood entering the fistula is reduced, diminishing both the flow and the resultant thrill. Finally, in thrombosis, flow ceases entirely, causing the thrill to vanish because no blood can traverse the fistula.

Bruit: A bruit is the audible manifestation of turbulent blood flow within the AVF. Normally, because arterial blood flows directly into a vein at relatively high velocity, you’ll hear a low-pitched, continuous murmur throughout both systole and diastole. When there is stenosis, blood must move through a narrowed segment at higher velocity, creating more pronounced turbulence. However, as arterial pressure drops in diastole, the increased resistance at the stenosis can dramatically reduce or halt blood flow during that phase, causing the diastolic component of the bruit to vanish. In severe stenosis or near-complete occlusion, the bruit may diminish greatly or disappear altogether because there is little to no flow. Handheld continuous-wave Doppler ultrasound can help pinpoint the location and severity of stenosis or confirm occlusion by detecting absent flow signals.

Special exams

Arm elevation test: When the arm is raised above heart level, venous pressure in the upper extremity drops, promoting free drainage of blood through a normal AVF, which then collapses. In a stenotic AVF, however, the narrowed outflow path impedes venous drainage. As a result, the fistula remains distended despite the reduction in hydrostatic pressure, signaling an obstructive lesion. (Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UzkXAB3pYSU)

Pulse augmentation test: The test is performed by gently compressing the venous outflow segment of the AVF while palpating the pulse over the access. In a normal fistula, blocking the outflow briefly increases the pulse amplitude, because arterial inflow continues to deliver blood while venous outflow is restricted, raising pressure within the fistula. If there is significant downstream stenosis or other flow-limiting pathology, compression may not produce a noticeable increase in the pulse, as the fistula is already under higher pressure and cannot augment further.

Table 4 outlines common physical exam findings, distinguishing between normal results and those indicative of stenosis, to aid in detection and management.

| Arm elevation test | Pulse | Thrill | Bruit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Collapses normally | Absent or soft, easily compressible | Present, diffuse, soft | Low-pitched, soft, rumbling, with both systolic and diastolic component |

| Venous stenosis | Fails to collapse | Increased, forceful | Strong, prolonged at stenotic site | High-pitched, systolic |

| Arterial stenosis | May partially collapse | Weak or absent distally | Diminished or absent near stenosis | High-pitched, systolic, diminished flow |

| Thrombosis | Fails to collapse | Absent | Absent | Absent |

Table 4: Physical exam findings to distinguish between stenotic and thrombotic lesions of AV access.

“Look, feel, listen:” The physical exam should include inspection, palpation, and auscultation as it can easily detect common fistula problems.

Routine Monitoring

Routine monitoring during dialysis sessions and weekly clinical assessments with physical exams, as outlined in the 2008 Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) guidelines, identifies problems early and helps maintain AVF function. (Sidawy et al. 2008) Clinical signs to watch for include cannulation difficulties, prolonged bleeding, infiltrations, brusing, or clot aspiration during dialysis.

Dialysis efficiency is often tracked using two measurements: Kt/V and the Urea Reduction Ratio (URR). Kt/V is a dimensionless ratio that relates dialyzer clearance (𝐾) with treatment time (𝑡) and the patient’s total body water (𝑉); a typical target for adequate dialysis is a Kt/V of 1.2–1.4 per session. (Chen et al. 2023) URR, expressed as a percentage, measures the reduction in blood urea nitrogen from pre- to post-dialysis; a URR above 65% is generally considered acceptable. (Chen et al. 2023) Persistently low Kt/V or URR values warrant further evaluation.

When clinical concerns arise, ultrasound or other imaging modalities can be used to confirm abnormalities. Elective secondary procedures, such as angioplasty or thrombectomy, can salvage AVFs that fail to mature. Early referral to a vascular surgeon, interventional radiologist, or interventional nephrologist, is essential to ensure timely intervention.

Surveillance Methods

According to KDOQI guidelines, physical examination remains the cornerstone of AVF surveillance and is often the most practical and cost-effective method for early problem detection. (Lok et al. 2020c) Routine imaging studies for every patient are not universally recommended, but several additional surveillance methods, in addition to regular imaging, can supplement the physical exam when indicated:

- Intra-access blood flow monitoring: Using ultrasound or other flow-measuring devices, this technique evaluates blood flow within the vascular access. A flow rate below 400-500 mL/min often indicates stenosis, requiring further investigation or intervention. (Lok et al. 2020c) This method is particularly valuable for identifying inflow or outflow obstructions early.

Static dialysis venous pressure monitoring: Measures pressure within the venous limb of the dialysis circuit. Elevated pressures often suggest outflow obstruction, especially in AVGs. (Besarab et al. 1995) Persistently high pressures warrant further evaluation.

Complications and Outcomes

Edema

Swelling, particularly in the ipsilateral extremity, shoulder, chest wall, or breast, is a common complication following AV access surgery. Mild-to-moderate extremity swelling is typically seen after access placement and generally subsides over time. This transient swelling is often related to local inflammation or changes in venous hemodynamics due to the new access. Persistent or worsening swelling, however, may indicate underlying complications such as venous stenosis, CVS, or venous valvular incompetence.

Bleeding

Bleeding most often occurs intraoperatively or in the immediate postoperative period and is usually minor. In AVGs, intraoperative bleeding typically occurs at the anastomosis site or from needle holes in the graft material. These bleeding sites are generally controlled using hemostatic agents, such as thrombin, or by applying pressure. Persistent bleeding, however, should prompt evaluation for underlying coagulopathy or technical issues related to the surgical procedure.

Hematoma

Peri-access hematomas are a common postoperative issue following AV access surgery. Small, localized hematomas and ecchymosis around the anastomosis or graft tunnel are typically expected and resolve spontaneously within a few weeks. However, expanding hematomas, particularly in the postoperative period, often indicate a technical error, such as inadequate hemostasis or vascular injury. They can compress adjacent structures, leading to pain, swelling, compromised blood flow, or nerve dysfunction. These cases require prompt evaluation and, in many instances, a return to the operating room for surgical evacuation.

Seroma/Weeping Syndrome

Seromas, or pockets of serous fluid, can develop as a complication of AVGs. These result from ultrafiltration of plasma across the prosthetic graft, leading to fluid accumulation that can become firm over time. Seromas generally form slowly, often appearing within 30 days of graft implantation. While they are typically benign and may resolve on their own, seromas can predispose the patient to infection or disrupt graft function if untreated.

Failure of Maturation

Failure of maturation occurs when an AVF is unusable or fails within three months of initial use. (Asif, Roy-Chaudhury, and Beathard 2006) Approximately 30-50% of AVFs fail to mature without intervention. (Li et al. 2018) This issue often results from inflow or outflow stenosis preventing adequate AV flow for remodeling, which may preexist or arise after access placement. In some cases, these stenotic lesions can be surgically corrected, salvaging the AVF and progress to maturation. (Voormolen et al. 2009a) However, complete occlusion typically necessitates abandoning the access site. Risk factors include small or poor-quality veins and arteries, insufficient blood flow, advanced age, female sex, and coexisting conditions such as cardiac disease, peripheral arterial disease, pulmonary hypertension, diabetes, and obesity. (Kuningas and Inston 2021) (Wilmink et al. 2016)

Infection

AV access infections are low in incidence but are serious and potentially life-threatening complications. (Bylsma et al. 2017a) They are most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus (and less commonly Staphylococcus epidermidis). (Fysaraki et al. 2013) AVF infections typically involve needle puncture sites and often present as localized redness, warmth, and small pustules. (Benrashid et al. 2016) These superficial infections usually respond well to local wound care and antibiotic therapy. However, deeper infections, characterized by circumferential pain, swelling, erythema, and fluctuance, require systemic antibiotics and may necessitate surgical debridement to prevent further complications.

AVG infections are more common than AVF infections and more severe due to the synthetic material of the graft, which can act as a nidus for bacterial growth. A 4x incidence of infection in AVGs compared to AVFs have been reported. (Luís Coentrão et al. 2015) These infections usually necessitate complete graft excision with irrigation and possible vessel reconstruction. Some cases require staged reimplantation. Total graft removal is generally preferred to reduce the risk of recurrent infection. (Hisata et al. 2022) CVCs pose the highest risk of infection among access types with bacteremia and sepsis being common concerns.

The choice of cannulation technique is an important factor in managing infection risk. The buttonhole technique, which involves repeatedly cannulating the same site to create a tract, can reduce vessel wall damage but is associated with a slightly higher risk of infection. (Wong et al. 2014) In contrast, the ladder technique rotates cannulation sites along the length of the access, which helps minimize local trauma and lowers the likelihood of infection.

Stenosis, Thrombosis, and Patency

Patency is a critical measure of hemodialysis access durability and function. Primary patency refers to the interval from the time of access creation until the first required intervention, while secondary patency encompasses the total duration of access usability after any and all interventions to reestablish flow. AVFs typically demonstrate primary patency rates of approximately 60% at 1 year and 51% at 2 years, with secondary patency reaching 64% at 2 years. (Al-Jaishi et al. 2014) In contrast, AVGs often show lower patency rates of around 40% at 1 year. (Halbert et al. 2020)

Patency can be affected by numerous factors including infection, surgical technique and cannulation technique. These result in stenosis and thrombosis, distinct but interdependent complications in hemodialysis access that directly affect patency. Stenosis is clinically defined as narrowing of the vasculature lumen by a reduction of at least 50%. (Saad and Vesely 2004) Stenosis can independently lead to complete access occlusion but more often initiates thrombosis, the impetus for a cycle of occlusion. Stenosis increases shear stress and turbulence, promoting platelet aggregation and clot formation. Thrombosis, in turn, exacerbates local stenosis by creating further flow disturbances and neointimal hyperplasia. This vicious cycle can lead to rapid access failure without intervention.

Stenosis and thrombosis are often categorized into inflow and outflow problems based on their anatomical location and physiologic effects. Inflow complications arise from reduced blood entering the access. This is usually due to an arterial lesion or a lesion at the juxtaanastomotic portion of the fistula. Outflow complications stem from obstruction of venous return. The lesion can be in the outflow tract emptying the extremity or in the central veins.

The percent stenosis is calculated by comparing the narrowest lesion diameter to the adjacent normal vessel diameter.

AVF/AVG Stenosis

Stenosis typically occurs at sites of high turbulence, such as the venous outflow tract or central veins. Juxta-anastomotic stenosis (JAS) is the most common lesion in AVFs, typically located within 3-4 cm of the arterial anastomosis. Varying lengths of focal and diffuse stenosis can occur.

Clinically, stenosis is often detected through signs such as hyperpulsatility or diminished augmentation of the pulse. For example, a hyperpulsatile AVF indicates significant outflow resistance, while poor augmentation of the pulse may suggest inflow stenosis. The arm elevation test can also help distinguish stenotic from normal segments; in significant outflow stenosis, the distal vein remains distended when the arm is raised. Imaging modalities confirm stenosis and guide treatment. Duplex US is a preferred noninvasive method, while angiography provides definitive visualization of the stenotic segment and is often used during intervention. For a detailed description of physical exam findings and diagnostic approaches, please refer to Surveillance and Diagnostics and Imaging.

Stenosis is more common in AVFs than in AVGs and should be identified and corrected before thrombosis develops. Treatment for stenosis includes percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, stent placement, and surgical bypass. For a more detailed description, please refer to the Reintervention section.

Central Venous Stenosis (CVS)

CVS refers to venous obstruction within the central veins, such as the subclavian, brachiocephalic, or superior vena cava, that impairs drainage from the head and upper extremities The etiology often includes intimal injury from prior intravascular devices, external compression, or thrombosis. Pathophysiologic changes such as intimal hyperplasia, thrombus formation, or extrinsic compression contribute to luminal narrowing and obstructed flow.

The incidence of CVS ranges widely, from 3% to 60%, depending on the population studied and the presence of risk factors such as prior CVCs. (MacRae et al. 2005) (Lumsden 1997) It is more frequently symptomatic when associated with grafts and upper arm access compared to fistulas and forearm access. (Trerotola et al. 2015) Symptoms may include extremity or facial swelling, dilated collateral veins, and inadequate dialysis delivery. A venogramremains the diagnostic gold standard for confirming stenosis and identifying its etiology. For further information on physical exam findings and surveillance strategies, please refer to the Surveillance section.

Thrombosis

Thrombosis, or the formation of clot(s) within the access, is a leading cause of access failure. While AVFs are more resistant to thrombosis due to their native vessel composition, they are still at risk, especially when underlying stenosis is present. Other contributing factors include low flow rates, small arterial diameter, recurrent hypotension, hypercoagulable states, infection, female sex, fistula location (forearm > upper arm), and feeding artery (radial > brachial). Clinically, thrombosis presents as a sudden loss of thrill and bruit, difficulty cannulating the access, or inadequate dialysis delivery. Imaging, such as duplex ultrasound, is essential for detecting thrombus formation. Management options include percutaneous thrombectomy and open surgical procedures; however, severe or recurrent thrombosis may necessitate abandoning the existing access and creating a new one. Prophylactic anticoagulation has not been shown to effectively prevent AV graft thrombosis and carries a significant risk of bleeding, limiting its utility in this setting. (D’Ayala et al. 2008)

Thrombosis

Aneurysmal degeneration and pseudoaneurysms of AVF/Gs can compromise HD access. A true aneurysm involves dilation of all layers of the vessel wall. Although various definitions exist in the literature and there is not one universally agreed upon, many sources define an aneurysm as a focal enlargement of the vessel diameter exceeding 1.5 to 2 times the caliber of the native mature vein. (Mudoni et al. 2015a) (Shah, Vachharajani, and Agarwal 2013) In contrast, a pseudoaneurysm (false aneurysm) results from a disruption of the vessel wall, blood extravasates from the injury site and is contained by a wall developed with the products of the clotting cascade. (Rivera and Dattilo 2025) Repeated cannulation in the same area is a common cause of pseudoaneurysm formation. Other contributing factors include high-pressure flow, thin or compromised vessel walls, and infection.

Both aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms can compromise vascular access by distorting normal flow and limiting cannulation sites. More concerning are the risks of rupture, infection, and hemorrhage, which can lead to life-threatening emergencies. According to multiple guidelines, urgent surgical consultation is necessary when:

- The skin overlying the fistula is compromised or ulcerated

- There is a risk of fistula rupture

- There are rapid size increases

- There is uncontrollable bleeding

Treatment strategies include aneurysm resection with interposition grafting , primary end-to-end repair or aneurysmorrhaphy. Preventive measures focus on rotating the sites of needle insertion to minimize repeated stress on the same segment of the vessel or graft. Proper cannulation technique, coupled with patient education, can significantly lower the incidence of aneurysm formation.

High-Flow Heart Failure

High-flow AV access can exacerbate congestive heart failure due to increased shunting, leading to central venous overload. (Roca-Tey 2016) This complication happens from imposing strain on the heart when excessive AV flow reduces systemic vascular resistance with a subsequent compensatory increase in cardiac output. Patients with high-flow heart failure may present with dyspnea, orthopnea, fatigue, and physical findings such as a large, distended AV access with strong pulse augmentation and thrill. Evaluation includes AVF duplex US to confirm high flow rates (>2000 cc/min). Echocardiography often reveals inferior vena cava dilation, right ventricular dysfunction, and increased pulmonary artery pressures. Right heart catheterization is the gold standard to detection. It can confirm hemodynamic changes, with transient AV compression showing reductions in cardiac output and central venous pressure, although PA and pulmonary capillary wedge pressures may remain stable due to increased afterload from access occlusion.

For patients with Stage C heart failure (NYHA Class I or II) who need dialysis, radiocephalic AVFs are preferred over brachial AVFs, and end-to-side anastomosis may help limit flow. (Bourquelot 2016a) For those with more advanced heart failure (NYHA Class III or IV, Stage D), tunneled catheters are recommended to minimize cardiovascular strain. (Bourquelot 2016a)

Flow reduction is central to managing high-flow heart failure. Surgical options include banding to constrict the AV access, plication to reduce lumen size, distalization of inflow to redirect arterial flow, or complete ligation in severe cases where preserving the AV access is not feasible. (Davidson et al. 2003)

Hemodialysis Access-Induced Distal Ischemia (HAIDI)

Hemodialysis access-induced distal ischemia (HAIDI) encompasses a spectrum of ischemic complications resulting from vascular access creation. These include dialysis access steal syndrome (DASS) and ischemic monomelic neuropathy (IMN). Although uncommon, HAIDI can cause significant morbidity, including limb dysfunction, pain, and, in extreme cases, limb loss.

HAIDI results from decreased distal blood flow due to diversion of arterial blood through the arteriovenous (AV) access. This phenomenon is exacerbated in patients with compromised distal circulation and increased flow demands of the AV access. The result is reduced perfusion to the distal extremity, which manifests as ischemic symptoms.

Several factors predispose patients to HAIDI, including:

- Use of the brachial artery for access.

- Female sex.

- Diabetes mellitus and atherosclerotic disease (CAD, PVD).

- Advanced age.

Dialysis Access Steal Syndrome (DASS)

DASS is the most common form of HAIDI, with symptoms ranging from mild paresthesia and coolness to severe ischemia with pain, weakness, and tissue loss. Symptoms often worsen during dialysis due to increased flow demands. Physical examination can identify DASS by manually compressing the AV access, which improves distal perfusion and symptoms. Noninvasive testing, such as duplex ultrasound with and without fistula compression, can evaluate waveforms, finger pressures, and flow patterns.

Treatment options include increasing resistance within the AV flow circuit using precision banding procedures (e.g., the minimally invasive limited ligation endoluminal-assisted revision (MILLER) technique), which helps redistribute blood flow to the distal extremity. (Goel et al. 2006) During the MILLER procedure, a balloon is expanded in the vein so it can be localized on the skin and small incisions can be made to get a band around the vein. The band is then tightened under duplex ultrasound guidance to optimize blood flow to the hand while maintaining sufficient access flow for dialysis. Banding procedures can be done in conjunction with flow measurements to achieve desired flow reduction. Other options include flow reduction methods and revascularization strategies such as distal revascularization interval ligation (DRIL), proximalization of arterial inflow (PAI), revision using distal inflow (RUDI).

In cases of severe ischemia or failed revascularization, AV access ligation may be necessary.

Ischemic Monomelic Neuropathy (IMN)

IMN is a rare complication of vascular access, occurring in less than 1% of cases. (Thimmisetty et al. 2017) It arises due to poor perfusion of the nerve sheaths in the radial, ulnar, and median nerves. Unlike DASS, IMN is characterized by the acute onset of severe hand pain, sensory loss, and motor deficits immediately following access placement. Neurological deficits, such as nerve palsies resulting in wrist drop and impaired intrinsic hand muscle function, often progress to claw hand deformities if untreated. IMN is differentiated from DASS by the absence of tissue ischemia, preserved pulses, and warm distal extremity [Table 5]. Electromyography reveals signs of acute denervation. (Miles 1999) Immediate ligation of the vascular access is the treatment of choice. (Lok et al. 2020c) Unfortunately, even with timely intervention, most patients experience incomplete recovery.

| DASS | IMN | |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Insidious | Acutely after access placement |

| Symptoms | Cool, weak, painful | Weak, painful |

| Radial pulses | Weak or absent | Preserved |

Table 5: Differentiation of symptoms in DASS and IMN

Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis, or calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a rare but life-threatening vascular calcification disorder most commonly seen in patients with ESRD undergoing dialysis. It is characterized by calcification of small- and medium-sized arterioles in the dermis and subcutaneous fat, leading to tissue ischemia, necrosis, and non-healing ulcers.

The condition typically presents with painful, violaceous skin lesions that rapidly progress to indurated plaques, ulceration, and eschar formation, most commonly involving the thighs, abdomen, and buttocks . Secondary infection of the necrotic tissue is a frequent complication and a major cause of mortality. The diagnosis is clinical but can be confirmed with a skin biopsy showing medial calcification of arterioles, intimal proliferation, and thrombosis. Biopsy is generally avoided in clinically obvious cases due to the risk of poor wound healing.

Access Recirculation

Access recirculation occurs when blood that has already been filtered by the dialysis machine flows back into the arterial lumen of the access circuit instead of returning to the systemic circulation via the venous outflow. This process arises when vascular access blood flow falls below the rate required by the dialysis pump, causing flow reversal between the arterial and venous needles. Contributing factors include poor arterial inflow, venous outflow obstruction, or improper needle placement. Recirculation results in the reprocessing of the same blood, which limits toxin removal and compromises dialysis efficacy, efficiency, and solute clearance and can result in an increased risk of morbidity and mortality. (Tal 2005) Recirculation can be identified through clinical signs or duplex US and flow measurements. Management includes correcting needle placement, surgically addressing stenotic lesions, and adjusting blood flow rates to match the access’s capacity.

Central Venous Catheter-Specific Complications

While CVCs are susceptible to general complications such as infection, stenosis, and thrombosis, there are unique risks inherent to this form of dialysis access. These include:

- Pneumothorax and hemothorax

- Mechanism: Occurs during insertion into the ICA due to inadvertent puncture of the pleura, subclavian artery, or innominate vein or artery injury.

- Presentation: Dyspnea, hypoxia, hemodynamic instability.

- Prevention: Use US guidance during catheter insertion and proper technique to avoid vessel or pleural injury

- Management: Chest X-ray or US confirmation followed by needle decompression or chest tube placement, as required.

- Mechanical obstruction

- Mechanism: Catheter malposition, migration, kinking, or fibrin sheath formation.

- Presentation: Reduced or absent blood flow through the catheter, increased resistance during dialysis, or inability to aspirate or flush.

- Prevention: Proper catheter placement and routine monitoring of catheter function.

- Management: Repositioning, catheter exchange.

- Catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs)

- Mechanism: Pathogens from the catheter surface or exit site enter the bloodstream.

- Presentation: Fever, chills, erythema, or purulence at the catheter site.

- Prevention: Strict adherence to sterile technique during catheter insertion and maintenance.

- Management: Blood cultures to confirm infection, systemic antibiotics, and catheter removal or exchange.

- Air embolism

- Mechanism: Air enters the venous system during catheter insertion or removal.

- Presentation: Sudden dyspnea, chest pain, or cardiovascular collapse.

- Prevention: Position the patient in Trendelenburg during access manipulation.

- Management: Immediately position the patient in the left lateral decubitus position with the head down (Trendelenburg), and attempt to aspirate air from the central venous catheter, administer oxygen .

- Venous stenosis and thrombosis

- While not unique to CVCs, the high incidence of central vein injury makes these complications more common with catheter use. Prolonged catheter placement increases the risk of CVS or occlusion.

- Dialysis-associated dysrhythmias

- Mechanism: Contact of the catheter tip with the atrial or ventricular wall can induce arrhythmias.

- Management: Withdraw the catheter to reposition its tip.

Reintervention

Reintervention plays an important role in maintaining HD access through personalized strategies that address both immediate clinical needs and long-term planning. Approximately 70% of patients with HD access require reintervention within the first year, highlighting the importance of continuous monitoring and proactive management. (Lawson, Niklason, and Roy-Chaudhury 2020) The focus extends beyond resolving current dysfunction to ensuring future access reliability through advanced planning. Effective reintervention requires a forward-looking approach that integrates the patient’s overall health goals, timeline for dialysis dependency, and potential challenges in creating alternative access. (Lok et al. 2020c) A commitment to proactive planning, such as evaluating backup access sites early and engaging patients in shared decision-making, ensures not only the salvage of current access but also continuity of treatment.

Reintervention is warranted when clinical signs such as declining dialysis efficiency and symptomatic abnormal physical exam findings indicate access dysfunction. Complications requiring reintervention, previously detailed in Complications, include failure of maturation, stenosis, thrombosis, aneurysmal degeneration, heart failure, and ischemic symptoms. Incidental lesions detected on imaging are generally monitored unless symptomatic.

Comprehensive imaging and clinical assessments are essential before any reintervention. Angiography remains the gold standard for evaluating the anatomy of the entire access circuit, from the arterial inflow to the superior or inferior vena cava, as multiple lesions are often present. Following treatment, it is crucial to reassess the clinical or physiological abnormalities identified pre-procedure. Successful intervention is marked by the resolution of these abnormalities and the restoration of adequate dialysis function.

Endovascular Reinterventions

Endovascular interventions are the cornerstone of minimally invasive treatments for HD access complications, particularly for stenosis and thrombosis. Angioplasty, the primary modality, involves the inflation of an intravascular balloon within a stenotic segment to restore luminal patency. Procedural success is defined as achieving less than 30% residual stenosis after the procedure when compared to adjacent normal veins on imaging. (“Clinical Practice Guidelines for Vascular Access” 2006) Complications such as venous spasm or vein rupture occur in <1% of patients, though they are typically managed effectively with interventions like balloon tamponade or the placement of covered stents. (Beathard, Urbanes, and Litchfield 2017) Percutaneous thrombectomy and catheter-directed thrombolysis are valuable adjuncts to angioplasty as they can promptly address complications without requiring surgical revision, thus maintaining continuity of dialysis treatment. Stent placement is reserved for cases of reintervention failure due to the risk for complications. Indications include acute angioplasty failure, rapid recurrence, and vein rupture following angioplasty. (Dariushnia et al. 2016) For cases of CVS, initial treatment often involves balloon venoplasty, with stenting reserved for similar situations as patency rates following venous stenting are relatively low. (Dariushnia et al. 2016)

When addressing AVF maturation failure, Balloon-Assisted Maturation (BAM) employs serial angioplasties to enlarge veins that fail to dilate naturally. Although BAM results can be variable, it remains a preferable option to access abandonment. However, AVFs requiring BAM often demonstrate decreased cumulative survival and higher reintervention rates compared to those maturing without intervention. (Lee et al. 2011)

Open Reinterventions

When endovascular techniques are insufficient or inappropriate, surgical options are explored. These include neo-anastomosis creation, vein-to-vein reanastomosis, and interposition grafts using PTFE or bovine carotid grafts (for example, the Artegraft from LeMaitre) for a variety of indications. While effective, these approaches carry higher risks of infection, discontinuity in HD access, and potential abandonment of the original access.

For recurrent stenosis requiring more than two angioplasties in three months or symptomatic central venous occlusion unresponsive to stenting, open surgical revision may be necessary. (Lok et al. 2020c) Physicians can attempt to salvage the original access with embolectomy, interposition graftting , or abandonment the AVF/G altogether. Surgical intervention of ischemic complications like DASS are discussed in Dialysis Access Steal Syndrome.

Similarly, symptomatic heart failure secondary to high-flow AV access can be managed with flow reduction by banding, plication, and distalization of inflow. (Bourquelot 2016b) In severe cases, complete ligation with creation of new access may be necessary.